Tattooed women outnumber their male counterparts, but cultural stereotypes and historical realities about tattooed women can cloud perceptions.

by S.E. Curtis

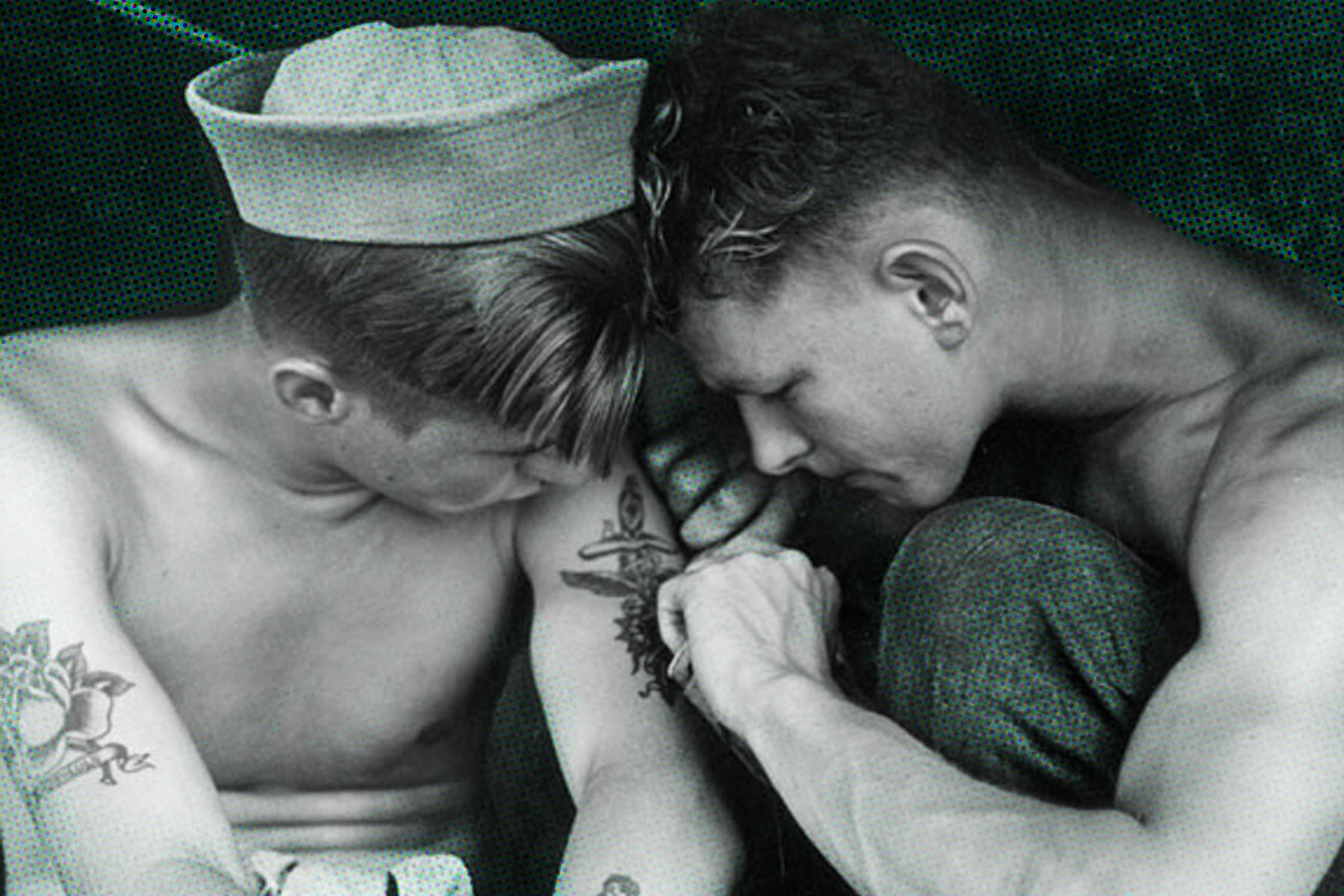

photo illustration by Grace Molteni

“What’s that?” An old man’s finger is inches away from my décolletage. He and his wife are standing in front of my table in my neighborhood coffee shop. I am literally trapped in a corner.

“It’s a tattoo.” I take off my headphones.

“Is that your boyfriend’s name?”

“It’s from a book.”

“What’s it going to look like when you get old?” The man’s wife asks.

“Well, I don’t know. The same way the rest of me looks? Faded? Wrinkled?”

Even though I’ve been tattooed for more than a decade (I’m 28), I never know how to react to strangers asking about and commenting on my tattoos. I feel like they’ve stolen my diary and are asking me to explain the entries. These moments put me on display—like I’m Lydia the Tattooed Lady. Except that I’m not entirely covered in body art and most of my pieces aren’t as elaborate or intricate as the woman in Groucho Marx’s song. People who ask me about my tattoos tend to be in their 50s or older and, in a way, I think their inquisition and comments are an effort to try and understand what’s going on with people (especially women) my age.

A Pew poll from 2010 reported that around 38 percent of Millennials and around 32 percent of Generation Xers have tattoos. These numbers indicate that body art and modification is simply more common than it has ever been among adults in the United States. These statistics, paired with a quick walk through one of the more tattooed cities like Austin, Texas or Richmond, Virginia, should illustrate why invasive gawking and inquiry should die out. Tattoos are ubiquitous and thus, ideally, should not warrant excitement.

I asked Margot Mifflin, the author of Bodies of Subversion: A History of Women and Tattoo (the third edition of which was published in 2013), about why older people find it so necessary to ask tattooed young people about their ink. “This is the comment of someone who may not understand that a whole demographic of people are going to share tattoos on aged bodies, which may indeed look worn and stretched, just liked aged bodies look worn and stretched,” she says. “I think on some level this is an expression of older people’s anxiety about their own aging bodies.”

For the Baby Boomers (and the Silent Generation) before them, a woman’s marriage, family, and related social or economic indicators largely defined who she was. However, traditional permanence and the idea of “settling in” is no longer the norm. Generation Xers and Millennials grew up in the wake of the highest divorce rates;they are also less likely to have one job all of their lives, or to own a home. The growing number of tattooed young adults is indicative not of the negative signifiers of the past: gang affiliation, lower-class standing, criminal history, or exhibitionist tendencies. Instead, tattoos are a symbol of their struggle to find permanence in an ever-changing world.

Because Millennials and Generation Xers are less likely to use the same indicators as the generations before them, there is a gap concerning how to create a personal myth and definition. We build some of this identity online through social media. We can see where a person is from, what she looks like, who her family is, and what class she might belong to. Offline, we have indicators like tattoos, which are more likely to be personal reminders and symbols of our history than simple decorations or adornments. Sometimes, tattoos can act as both. Instead of the classic “Mom” over a heart, someone might choose more of a metaphor: their mother’s favorite flowers or an image from a favorite memory. We use our bodies as a means to express and create identity in ways that marital status, career, socio-economic standing, and other traditional societal markers don’t.

I asked Mifflin why she thought Millennials are getting more tattoos than other generations and she mentioned that the provocative nature of tattooing has lost a lot of its meaning. In the past, people got tattoos to show their allegiance to the counterculture or to stand out. It was a form of rebellion. “It’s harder for Millennials to be original than it was for previous generations, because so much is digitally shared and the information moves so fast, and because trends are commercialized and commodified so quickly.” According to Mifflin, tattoos are a way for a person in their 20s and 30s to self-define. This kind of body modification is less likely to be a statement about their cultural status or affiliations than it was in the past.

For tattooed young ladies like myself, another problem is contending with outdated views of femininity. Women are still held to higher and more specific standards of “decency” than men. We see it in the ways society deals with women on a daily basis. It’s common to ask about or remark on what the female victim of a sexual assault was wearing at the time, as if her outfit’s “level of decency” is any valid excuse or reasoning for the violence.

Even some feminists, who have worked for decades on securing a woman’s right to her own body, consider tattoos (and most body modifications) a form of mutilation and victimization. Andrea Dworkin, the late radical feminist icon and spokeswoman of the anti-pornography movement, contends that a tattoo can be the result of a subconscious hatred of your own body and a step in the direction of self-objectification. But this is at odds with how many women feel today about their bodies and the kinds of control we feel free to exert over them. Hannah Horvath, Lena Dunham’s character in HBO’s Girls, explains her tattoos as mostly a teenage reaction to feeling out of control of her body. In the pilot episode she says, “I gained a lot of weight very quickly and felt very out of control of my own body and it was just this Riot Grrrl idea of ‘I’m taking control of my own shape.’” Tattoos can be a way for someone to reclaim her body after a change or formative experience, whether physical or emotional.

In her book, Mifflin traces American women’s relationships with tattoos from the Victorian era to today. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tattooed women were often sideshow attractions in traveling circuses. Sometimes the “back story” of their tattoos focused on victimization (forced tattooing at the hands of Native American captors or abusive men). Those stories, which were often debunked, were used to create a sense of drama and salaciousness around the women, which made them more of an attraction. This is in contrast with the tattooed men of that time—most of whom were in the military, specifically the Navy. Tattoos on a sailor were meant to tell the story of where he had been and what he had achieved. They also served to identify his body. Being a “Tattooed Lady,” according to Mifflin, became a way for a woman, probably from the lower or middle class, to become an independent entrepreneur by using the art on her body as an opportunity for economic self-reliance. Sometimes, this was an easier and more lucrative way to earn independence than other contemporary career choices like sewing or secretarial work.

Tattoos on these women often depicted patriotic or religious iconography, which were more culturally acceptable than “feminine” imagery such as flowers. Getting a tattoo of the Star Spangled Banner or Jesus showed devotion to her country or her religion and therefore wasn’t just vain decoration. However, cosmetic tattoos in the form of beauty marks, permanently shaped eyebrows, and fuller, rosier lips came into vogue among socially elite women in the 1920s. These same women, who might have also participated in the first wave of feminism, were also inspired to sometimes have smaller, dainty “adornment” tattoos around their wrists or in easily concealed places. But these two groups of women, Tattooed Ladies and the socially elite, comprised a very small population overall. In this time, tattoos were considered a manly form of expression because of the pain and risk involved. Not to mention that it was (and still is) more socially acceptable for a man to show his skin (tattooed or bare) than for a woman to do so.

By the late 1940s, however, tattoos of any kind, for both women and men, had become taboo because of hygiene and health risks involved in using needles. This, along with the shift to a more conservative culture in the 1950s, influenced how people felt about tattoos. The fact that the most infamous tattooed women were attractions in freak shows didn’t jive with the turn toward more conservative fashion and ideas of femininity. The Happy Homemaker of the 1950s wouldn’t dare venture into a tattoo parlor and take the risk. It wouldn’t have been considered ladylike or sophisticated to bedazzle oneself with a permanent tattoo.

These trends sent many tattoo artists underground, which only reaffirmed the public’s conception of a lack of hygiene and safety involved with tattooing. The mid-century ushered in the idea that tattoos were dangerous and meant for criminals and rebels; those people who were willing to risk their lives for body modification. Women were even less likely in the 1940s up through the ‘60s to have a tattoo than their male counterparts. In many places in the U.S., tattoo parlors were banned during the 1950s and 1960s. New York City, for example, declared a prohibition on tattooing in 1961 and didn’t re-legalize it until 1997. I got my first tattoo in Norfolk, Virginia, home of the largest Navy base in the world. The city banned tattooing in 1950 and didn’t allow it again until 2005.The language of the ban, when it was instated, called tattooing “vulgar and cannibalistic.” Even when it was lifted, the city government still regulated where a tattoo parlor could open.

Because tattoos were often illegal to obtain, it wasn’t until the late 1960s that they began to reemerge as a more common form of body modification, but only for some people. During this time, tattoos were considered a symbol of lower socio-economic standing because of the underground and sub-cultural presence. Paul Taylor writes in his 2014 book, The Next America: Boomers, Millennials, and the Looming Generational Showdown: “Back in the day, tattoos were the body wear of sailors, hookers, and strippers. Today they’ve become a mainstream identity badge for Millennials.” Taylor, a Baby Boomer himself, mentions two generally female occupations, strippers and hookers, and only one typically male occupation, but it’s only been in the past few years that the population of tattooed women (23 percent) has overtaken that of tattooed men (19 percent). Maybe that’s why the people who associate tattoos with working and lower class people are surprised and intrigued when they see me working at the public library or when they see my tattooed friend working as the executive director of a local investing organization—let alone the hype caused by someone like Jill Abramson when she was executive editor of the New York Times. In all cases, discussion of thesetattoos, their origins, andtheir meanings was imminent.

Today, tattooing is decriminalized in all 50 states and tattooing hygiene and safety regulations are often folded into the Department of Health’s jurisdiction. Tattooed people in the modern workplace enjoy fewer restrictions on self-expression. A Careerbuilders.com poll reported that piercings and bad breath ranked higher as reasons for not hiring or promoting an employee. Visible tattoos and disheveled clothing tied for third place.

Yet, the negativity that follows the culture of tattoos and, specifically, the allure and exoticism of the tattooed lady, has yet to diminish. An older friend of mine, a proud second-wave feminist, brought up that people see my tattoos as an invitation. I asked her if, when she was my age, older women told her the same thing about the outlines of her nipples showing through her shirt after she burned all of her bras. For her, going braless was a statement that she made about having control of her body: she wouldn’t be controlled by that kind of physical and societal restraint. Similarly, my tattoos are a statement about my control over my body; I choose to modify it because it is mine to modify. Her assertion about tattoos being an invitation is a repercussion of the Tattooed Lady in the circus being on display for everyone to marvel at and learn from. But I am no spectacle; my stories are my own.

Sex is an inevitable topic when it comes to a woman exerting control over her own body. Paul Taylor’s statement concerning strippers and hookers having tattoos reveals a common assumption. Mifflin admits: “I do think the stereotype of the tattooed woman as looser than other women holds, from what some heavily tattooed women have told me about people who approach them and touch or comment on their tattoos presumptuously.” There has clearly been some kind of shift in societal stereotypes, though it may not be as progressive as we hope.

When shooting a wedding, my photographer friend Kate will often make sure that the families of the married-couple-to-be are ok with her wearing short sleeves to their ceremony. Her tattoos, her mother’s drawing of a spray of flowers that her tattooist traced onto her left arm; a rabbit from Good Night, Moon on the back of her neck; a mixed tape on the back of her left arm; and a camera on the back of her right, were all done by the same tattooist and bear incredibly deep meaning for her. She says that she has learned to bring up the possibility of revealing her tattoos in order to gauge what kind of crowd will be at the event. However, she also explains, “If I’m wearing a three-fourths-length cardigan at an outdoor wedding in July in the South, it may affect my level of comfort and therefore my ability to shoot. So there has to be some compromise.”

There are other situations in which Kate will cover up her tattoos. When she is going to meet the teachers of her daughter, Fiona, for example. She does this so these people have a chance to formulate an opinion on her before they find out she has tattoos. Kate admitted that when she takes Fiona to the playground, other women—sometimes loudly—question her ability to be a good influence on her daughter. Similarly, Sarah, another friend of mine who works on a book mobile in a small town in Ohio, expresses incredible anxiety when thinking about going to a job interview or meeting people for the first time. “I make sure that my tattoos are covered so that I don’t have to have the conversation about ‘where, when, why, and how’ with these people until they know me better,” she says.

Recently, Sarah started working in a new position and still hasn’t worn anything that would reveal her tattoos. “I work with all these older white women…they have said some things about tattoos that made me feel awkward.” Her co-workers gossip about a Pre-K teacher who has a “trashy neck tattoo,” saying she “shouldn’t be displaying tattoos in front of children.”

Though the external indicators for Sarah and Kate are those of educated, middle-class people, their tattoos cause anxiety for others, which the tattooed women are forced to respond to. Having visible tattoos commands the eye in a non-traditional way. Instead of starting at the face and traveling down the body—noting hair, makeup, clothes, etc.—a tattoo might reroute a person’s presumptuous gaze. This sends the onlooker into a feeling of anxiety. The presence of the tattoo might not align with traditional indicators of class, education, or profession. Someone might presume what kind of person a woman is by her profession, clothes, hair, makeup, etc., all of which suggest one category while her tattoos suggest another.

Kate admits that when she is photographing and styling for a company, more people ask her about her tattoos than those of her male counterparts. “I feel like women are looked at more, and more judgments are made on the basis on what we’re wearing and what we look like,” she says. “You can easily dismiss a man’s outfit and his tattoos—chalk it up to manliness. But when you see my tattoos you ‘have to ask’ as if my reasons and history are more interesting than that guy’s.”

In my own experience, people take great umbrage when I dodge their questions about my own tattoos. Though my eight tattoos are easily covered, I don’t often choose clothes that will hide them. This is less for provocation and more for comfort. For the first year that I had visible tattoos, I lived in a neighborhood of Brooklyn where tattoos were ubiquitous. No one ever looked twice at my tattoos or brought them up in conversation. That experience left me a little naïve as to how people in other parts of the country would react. I placed trust in the unspoken pact of “don’t ask, don’t tell” when it came to tattoos. In Brooklyn (or Richmond or Austin, etc.), it’s considered pretty uncool, if not downright rude, to ask a stranger about her tattoos. A person who asks generally doesn’t know what they are getting into. My most prominent tattoo, the word “timshel.” in American Typewriter font, drapes around my décolletage like a necklace. Most people glaze over when I start to explain its meaning and origin. So I’ve made up a little conversation stopper which includes, “If I decided to get it put on my body permanently, don’t you think the explanation deserves more than a 10 second shrug between strangers?” That sounds dismissive, but keep in mind that these people don’t even know my name.

Tattoos are more common and more acceptable now in the United States than they have ever been. Older generations, however, still consider them taboo, exotic, or warranting of comment and inquiry. Is it just the inevitable generational gap? The feeling I get now, when talking to tattooed people in their 20s and 30s, is that there will be little or no regret when their tattoos begin to fade and wrinkle along with their skin. Meanings change, yes. What was important in your early 20s may not hold the same weight when you’re older. But, in general, they see their tattoos as badges and milestones.

How do I explain that to a stranger who carries preconceived conceptions about tattooed people? I realize that the history of tattooed women up until this point is what leads people to these conclusions. Rightly or wrongly, these women were considered by society to be risk-takers, criminals, victims of abuse, parts of freak shows, and property of gangs. But this assumption glosses over what tattoos have evolved into for women. When I turn 35, I may not be married or have children. I probably won’t own a house or have the same job. I may not live in the same town or have the same friends. I may not even own the same records, books or clothes. But I do know that when I look in the mirror at my back, legs, arms, neck and décolletage, I will see the people, places, and moments I’ve known and experienced. I might not be able to carry photo albums or keepsakes around when I move, but I will have these tattoos—weightless reminders of who I have been and what I have seen. When I’m 65, those reminders will fade, wrinkle, and change just like the rest of me. Asking me to regret them or fear what they might look like is asking me to regret being a woman and having a body that changes with time.

[hr style=”striped”]

S.E. Curtis is a writer, reader, cook, and Southern culture optimist. Her devotions include: participating in micropolitan life in the Shenandoah Valley, dreaming of Live Oaks and Spanish Moss, and cooking various delicacies in her beloved cast iron skillets. To contact or learn more about her please visit her personal website or on Twitter.

Grace Molteni is a Midwest born and raised designer, illustrator, and self-proclaimed bibliophile, currently calling Chicago home. For more musings, work, or just to say hey check her out on Instagram or at her personal website.