A rebellious teen fights to survive girlhood in the rougher New York of the 1970s.

by Joanna Demkiewicz

No one needs to be reminded that adolescence is hard, but the nuances are often difficult to capture, let alone relay. Girlhood, especially, is filled with secrets, a fleeting sense of control, and the dizzying newness of sexuality.

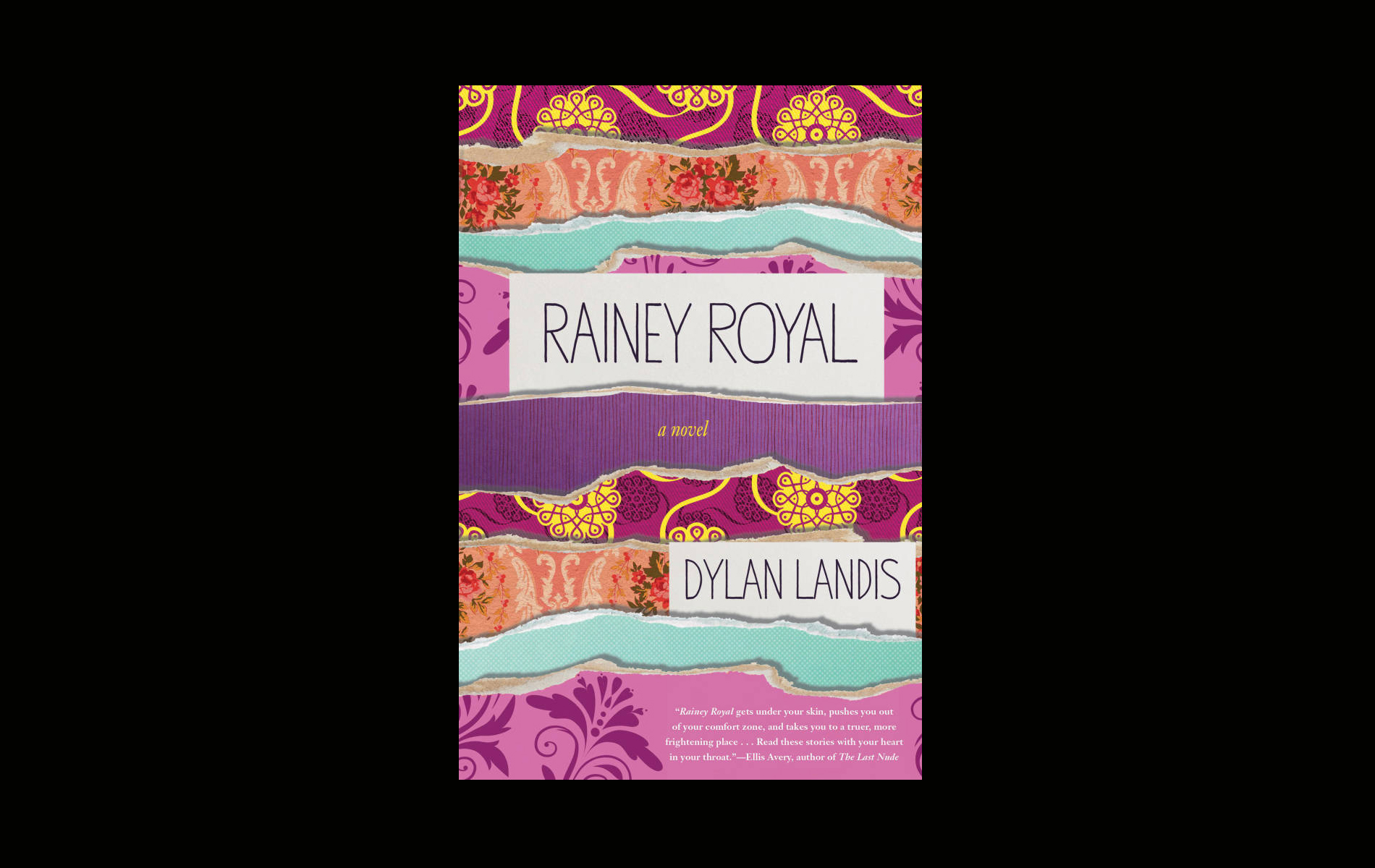

Author Dylan Landis’s girlhood took place in New York City in the 1960s and ‘70s, where “it was slack and permissive and decadent, and parents had no idea what was going on.” Landis’s nostalgia for this particular time, place and age is the foundation for Rainey Royal (Soho Press), a novel–or rather, a series of short stories spanning from 1972 to the early 1980s – that gives girlhood an intimidating and mesmerizing heroine.

Rainey Royal is a contradictory character, and we are lucky enough to be given the secrets no one else can touch. She keeps them locked away in her brutally pink-wallpapered room–so pink, in fact, that the first time her best friend Tina visits she can’t help but blurt, “Oh my God you live in a vagina.”

The room represents Rainey’s fleeting persistence with control – it’s fleeting because some of the ugliest secrets take place here. Rainey uses her sexuality and commanding body to control what she can, because, in fact, she cannot control everything that happens because of them. “Rainey loves how she and Tina can sit in certain ways and force certain male teachers to look at them,” we learn just after a scene in which Rainey’s dad’s best friend sneaks into her room to stroke her hair and back while Rainey pretends to be asleep.

The friend–Gordy–lives with Rainey and her dad Howard. Gordy’s bedroom is on the same floor of the Greenwich Village brownstone as Rainey’s, and apparently this tuck-in ritual is the norm. Rainey, 14 years old when we meet her, “knows she is responsible for sending scent molecules swimming through some primal part of his brain.”

And so, here we go–Howard, the parent, has no idea what’s going on. Instead, he’s a busy, enticing clarinetist who finds young musicians on the street and invites them to live in his home so they can live and learn jazz 24/7. He often sleeps with the female acolytes, and that’s no secret.

A female flautist, in fact, is in Howard’s bed when Rainey bursts in one night after being raped by Damien, a cornet player. When Rainey asks her father to throw Damien out, Howard employs some bullshit “parenting” that we rarely see, despite the fact that Rainey often acts out and despite the fact that her school’s psychologist, concerned, calls Howard in after noticing Rainey flirting with male teachers.

“Listen,” Howard says. “Young men get confused about yes and no. I wish girls could understand that.”

And Rainey’s mother? She’s gone, escaped to an ashram in Colorado after feeling perpetually disappointed by Howard and sleeping with Gordy. Rainey reveres her mother; she wears her leftover tea-rose oil and her diamond ring, both attempts to feel connected to the woman who left her.

To Rainey, women are both enemies and allies. Because we are immediately introduced to Rainey as victim, we understand Rainey as a bully, or rather why she bullies. Landis interestingly describes Rainey, who first appeared as a secondary character in her 2009 debut novel, Normal People Don’t Live Like This, as “the most empowered character,” and indeed she wears power like a crown. Her best friend Tina, almost equally as frightening, is both witness and victim to Rainey’s bullying. In one chapter, entitled “Trust,” Rainey and Tina rob a young couple, a violent act that is actually a test of friendship and loyalty after Tina makes a bad joke about Gordy’s back rubs. They hold a gun to the woman’s back and manage to gain entry into the couple’s swanky apartment. They take the woman’s cape, the boyfriend’s watch and few sentimental photos and journal entries. The woman cries. The entire act is psychological and mature, dangerous yet mundane.

Landis’s time details–the cape, the lingering scent of sandalwood, the “normality” of a woman leaving her family for an ashram, the “normality” of a brownstone once gilded with chandeliers now serving as a dilapidated musician’s commune–are accurate, at least according to Helen Schulman, author of two novels that take place in New York City. “Back then, we thought all the groping and seduction talk was something to endure, while Rainey sees it as a means to conquer,” Schulman writes for the New York Times Sunday Book Review.

Rainey does indeed conquer, but girlhood is not something you can win. And in the manner of someone who was never taught what to believe in, Rainey chooses to believe in Saint Catherine of Bologna, the patron saint of artists and against temptations. She reads about the patroness in the reading room of the New York Public Library and rips out her photo. A woman sitting across from her gasps.

“’Oh, relax,’” Rainey tells the woman as she opens the bag and slips the photo inside, a relic of her adolescence.

Joanna Demkiewicz is The Riveter‘s co-founder and co-editor. Find her on Twitter at @yanna_dem.