A look at what women, non-binary people and minorities are doing to solve the diversity issues in tech and where we can go from here.

By Anna Meyer

Illustration by Grace Molteni

Photographs by Sharolyn B. Hagen

The equity problem in the tech world isn’t a surprise to those who’ve been keeping track of the news or working in the field. Simply put, women, non-binary people and minorities aren’t being appropriately represented in technology related jobs. The National Center for Women & Information Technology reported that 26 percent of the computing workforce in 2016 were women, three percent of that African-American women, five percent Asian women, and two percent Hispanic women. These statistics beg obvious questions, among them: What is it like to work in an office where you’re one of the few—or are the only—woman, non–binary or person of color around?

Neem Serra, a 29-year-old developer in St. Louis, reflects on her first experiences in the industry while working at her previous job before she moved on to be a developer at a software company. In the first couple of weeks, she was asked out on dates by colleagues.

“People sort of jumped into not seeing me as a co–worker, but seeing me as a potentially datable person, which is just really awkward,” says Neem Serra. “[People] made a lot of comments about what I was wearing. It was honestly just really uncomfortable.”

Alongside her junior standing and age, being one of the few Asians in her office influenced how she was treated. “People would ask me questions like, ‘Oh, where are you from? I’m surprised that you speak English so well.’ I don’t think people mean poorly by it or anything, but it’s things like that that make you go, ‘Okay, this is not going well. You are not asking other co-workers this,’” she says.

Serra’s experience reflects many. Well-known stories coming out of Silicon Valley tell of Uber’s culture of sexism and the infamous Google employee’s anti-diversity memo. Reading these stories and hearing personal accounts of all the ways tech is failing women, non-binary people and minorities makes it very easy to feel pessimistic about tech offices and practices.

But women and minorities are combating the diversity issues and doing something about the inequity it creates. Serra’s experiences led her to open a St. Louis chapter of Google’s Women Techmakers—a program that provides visibility, community and resources for women in technology. After five years, she left her previous company to be a developer at the consulting firm Slalom Consulting. “I actually picked the new company that I’m at because it’s led by a woman,” she adds.

Serra isn’t alone in her efforts.Advocates range from celebrities (Karlie Kloss hosts summer camps for girls through Kode with Klossy) to women working in tech who are ready to see change happen in their industry.

Creating Spaces

Kristen Womack, a product leader and technology consultant in Minneapolis, first noticed a difference between her and her male peers while working in corporate spaces. She noticed that she had to ask for promotions after succeeding in her work, whereas her male peers were handed promotions, sometimes for no clear reason.

“Or working on something all day and then having a man say, ‘Oh, I took it the last inch’ and then taking all the credit,” Womack says. “That made me want to just go out on my own, and [consider] leaving the industry.”

Additionally, Womack used her education in linguistics to identify how the words being used around her at work made an impact in power dynamics.

“I started paying attention to the fact that adult women were being constantly called ‘girls’ and the language that is used around men and women demeans women in a way that gave them less power,” she says. “So, as I started to experience this and notice what other women were experiencing, and since I feel that I have a loud voice, I just found myself speaking up more and more.”

Womack and Minneapolis-based engineer Jenna Pederson started the Twin Cities Geekettes, a chapter of a global community of women dedicated to help other female tech innovators be their best selves in their careers, inspired by what Womack calls a “snowball effect” of hearing women’s stories that were similar to her own. The chapter hosts hack nights where women create projects, as well as help cultivate a supportive professional network for women in the field.

“From the very beginning [Pederson and I] basically said, ‘We want to stop being invited to and going to panels where it was just talking and complaining about the problem, and we actually wanted to do something about it,’” says Womack.

When women who attended the Geekettes hacking nights expressed desire for more time to work on their projects to take them to the next level, Womack and Pederson co-founded Hack the Gap in 2015 to provide that time and space.

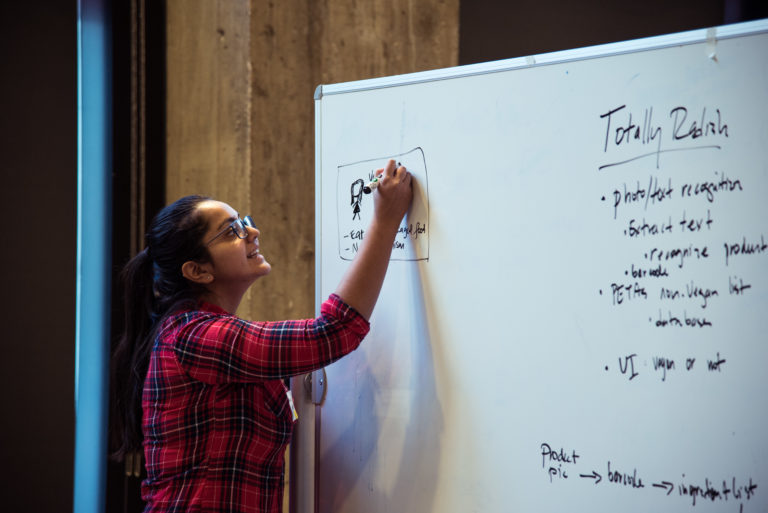

Hack the Gap is an annual weekend-long event where women and non-binary individuals can come together and work on projects in an accessible, supportive space. Winning projects can earn up to $1,500 as a prize. In the four years they’ve held the event, more than 250 women have participated in building 40 projects and/or applications. A mother-daughter duo that attended the event in 2016 even continued their project from Hack the Gap to found their own company, Medication Health. From 2018’s event in January, final projects included Totally Radish, a tool for vegans and those with restrictive diets to determine food’s contents from scanning a label, and Hustle, a platform that helps those with side projects find talented people to bring those projects to life.

Hack the Gap is headquartered in Minneapolis, but there are cases of spaces like it being created all over the country, sometimes called makerspaces or hackerspaces. When asked what’s accomplished in women-inclusive spaces as opposed to average workspaces, Womack says it has a lot to do with women’s sense of permission.

“Women tend to need more permission, because that’s how they’re conditioned in our society, she says. “When you put women together, everybody cares about each other and everyone cares about everyone having a role in the team, and working together, and they’re not … asking for permission. They’re all just diving in and they’re all socially in tune to be collaborative with one another.”

A key aspect of Hack the Gap’s message is to stop putting the blame on the pipeline—the idea that women aren’t in tech or signing up for degrees in tech fields simply because they’re not interested in the work. That’s simply not true.

“That [idea is] putting the blame back on the women,” says Womack.

Businesses Are Stepping Up

In the past four years, the registration for Hack the Gap has consistently sold out within weeks. Womack says she could barely keep up with sponsors for this year’s event.

When asked why a business would have an interest in supporting an event like Hack the Gap, digital agency GoKart Labs’ Vice President of Talent Amy Larson says it comes from first–hand experience.

“As a technology company, we see the gap in female representation first hand,” Larson says. “We want to create the kind of conditions and environments that better enable women’s participation. That can include encouraging and supporting girls in STEM–related education or giving women who choose those careers a path to success. Our hope is that by sponsoring and participating in events like Hack the Gap we can help move the needle in some way.“

CoderGirl, a St. Louis program that educates and engages women in tech, is an example of this bottom-up thinking. Nadia Copeland completed the program and made a successful late-career switch from nursing into tech. Copeland used her education and got hired at Boundless, a startup specializing on GIS theories and concepts. She mentions that her peers at Boundless have been supportive and encouraging through her career switch and employment.

As a step in the right direction, companies are taking initiatives to build relationships with educational programs and communities like CoderGirl in order to make the transition from the classroom into the workplace smoother. Mehul Patel, the CEO of hiring agency Hired, wrote for Entrepreneur in January that “companies can’t sit back and expect diverse talent to come knocking on their doors.” He stresses that engaging with communities—which in Hired’s case, includes Women Who Code and Lesbians Who Tech—is critical to creating diverse teams.

“It’s been inclusive and great,” Copeland says of her experience transitioning to Boundless. “That bad stuff is out there, but it’s like every time you hear about an airplane crash, that’s how I see it. You always hear when the bad stuff happens, and not when the good, and there’s a lot of good stuff that’s happening.”

CHANGES TO TRAINING

This approach to diversity issues is mirrored in the new trend of diversity training in businesses: unconscious-bias training. This training is aimed at changing the way we talk about interacting with and hiring minorities in the workplace—and it’s catching on fast. According to Time’s feature on the approach, 20 percent of companies in the U.S. now offer unconscious-bias training, including some big-tech names like Facebook and, ironically, Google.

The idea is that traditional diversity training in corporate offices is failing because it’s centered around guilt-tripping and finger-waving at white men.

“The training infuriates the people it’s intended to educate,” wrote Time’s Joanne Lipman. It also hurts minorities, in that they “leave training sessions thinking their co-workers must be even more biased than they had previously imagined,” Lipman wrote. “In a more troubling development, it turns out that telling people about others’ biases can actually heighten their own. Researchers have found that when people believe everybody else is biased, they feel free to be prejudiced themselves.”

Unconscious-bias training focuses on how exclusions happen most often due to unintended and unconscious biases. That’s to say, people are making mistakes because they’re simply unaware of its effects because they’ve never been on the receiving–end of the consequences. Through training, employees are taught to recognize those unconscious biases and fix them and their own behavior that’s been built on them. By bringing awareness to one’s biases rather than shaming them for it, the responses have been more effective.

It remains to be seen how this training will alter the tech industry’s makeup. While we wait, we have companies like Blendoor to keep Silicon Valley honest about what’s happening in their offices. Blendoor is hiring technology that hides data (like names, photos and ages of applicants) on applications that would trigger unconscious biases during the hiring process, which helps underrepresented groups level the playing field during the recruitment process. Blendoor also creates a “Blendscore,” which is a data-driven rating that evaluates a company’s equity, diversity and inclusion. As explained on Blendoor’s website, the rating is based on “demographics of the leadership team, retention statistics and strategies, recruiting practices, bias, and social impact initiatives.” They focus on “diversity of gender, race, ability and sexual orientation.”

Out of a score of 100, top companies include Intuit (86/100), Apple (81/100), HP (81/100) and Twitter (81/100). The lowest contenders include social media sites YouTube (13/100) and Tumblr (14/100).

On a more anecdotal scale, Serra has found that non-shaming approaches to target unconscious biases have worked for her in the workplace.

“The thing that has been most useful for me is just going and talking one–on–one with guys who are in positions of authority and telling them, ‘Okay, here’s what happened to me. And you know that I’m good at my job, but these are the things [that are happening,] and here are easy ways for you to stop that and make a different culture,” she says. “It sucks that I can’t just do it all on my own, but training allies is probably the thing that has worked the best for me.”

It’s problematic that women and minorities take on the burden of standing up for themselves in the diversity and inclusion fight. We live in a world of large adult sons that aren’t held to the same standards of responsibility as adult women, and minorities are tired of having to explain their oppression to those who are privileged enough to ignore it. Still, Serra is optimistic that the work of training allies is worth it.

“For every one woman that’s willing to fight, they end up talking about it to like, 10 dudes, and a percentage of them start to understand and start telling their friends,” Serra says. “We’re going to reach a tipping point at some point. It hasn’t happened yet, but I’m optimistic that it’s going to happen. When I hear rooms of guys calling out each other on it, I’m [optimistic.]”

Anna Meyer is The Riveter’s Digital Editor and a Minneapolis native currently calling Lawrence, Kansas home. She spends most of her funds on concert tickets, traveling the world and doing all things fueled by her daily espresso. Her work has also appeared in Clover Letter, Shine Text and Inc. magazine. You can stay updated with her work via her personal website.

Grace Molteni is a Midwest born and raised designer, illustrator, and self-proclaimed bibliophile, currently calling Chicago home. She believes strongly in a “beer first, always, and only” rule, and is forever seeking the perfect dumpling. For more musings, work, or just to say hey check her out on Instagram.