The film industry is shifting its approach to depictions of eating disorders.

By JoAnna Novak

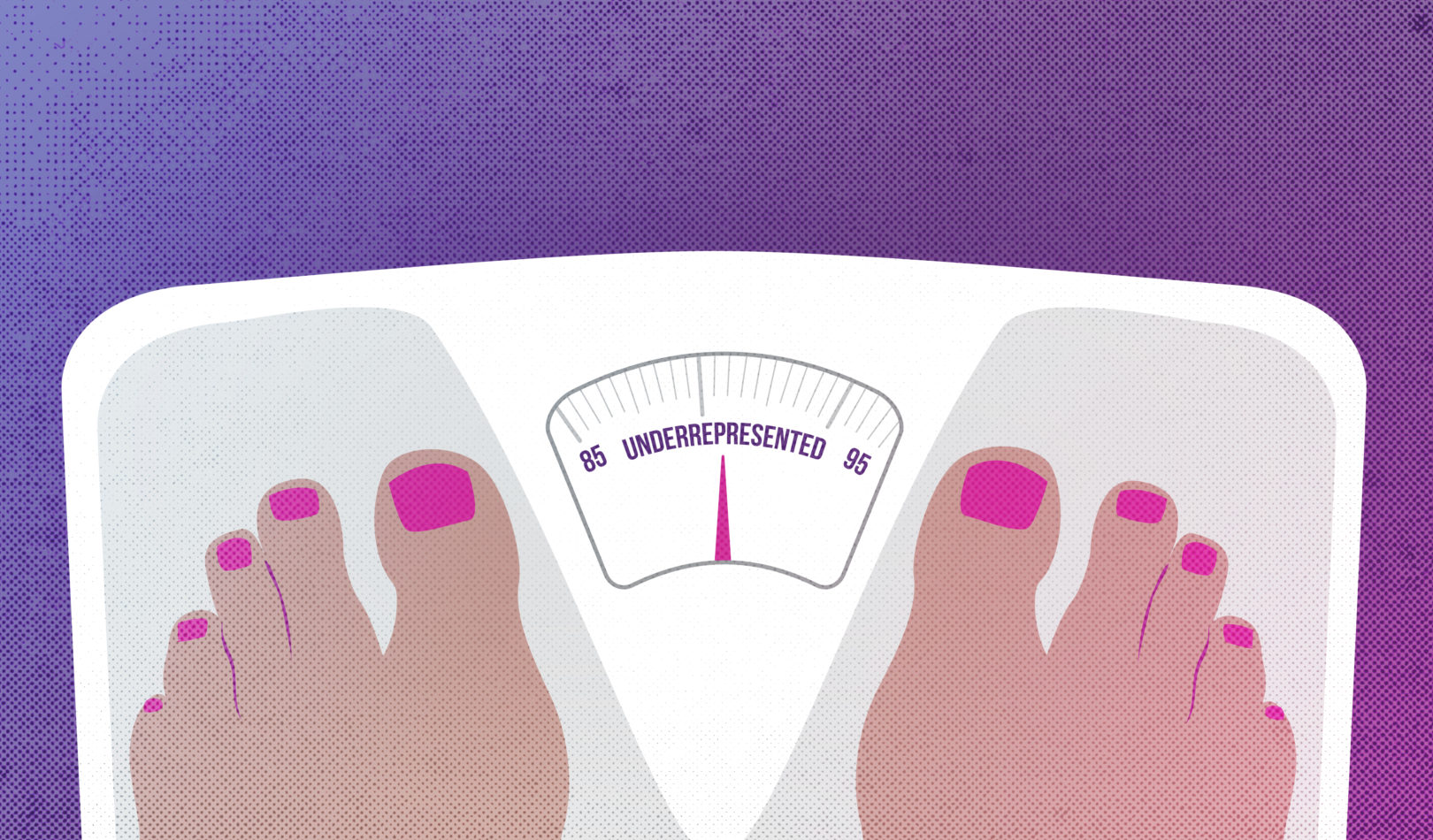

Illustration by Grace Molteni

I write nonfiction about my own eating disorder (ED) all the time, but my first novel, I Must Have You, is fiction—it isn’t autobiographical about anything except late-90s pop culture (#SavageGarden4Ever). The three characters who struggle with eating disorders represent different physical and emotional manifestations of EDs: Elliot, an eighth-grade diet coach, believes she can live with anorexia; her mother, Anna, a teacher, has bulimia that’s as routine for her as grading papers; and Lisa, Elliot’s best friend, who, at fourteen, has already been hospitalized for anorexia twice—and is beyond over having body image issues. In my own eating disorder, crisis came along every other year, when a new rock bottom opened beneath me like a trapdoor, but my characters’ climaxes never relate to their disorders. It can feel minimizing to downplay the crisis moments of an eating disorder, but the fact is one way we romanticize eating disorders is by doing just that—focusing on the heightened drama, the climaxes they produce.

I expected to be busy promoting the book when it came out in May, but I never expected to be doing so in the middle of a veritable barrage of eating disorders in film culture. That’s what it feels like, anyhow, with the release of two feature films, Marti Noxon’s To the Bone and Troian Bellisario’s FEED.

Recently, I was invited to a screening of FEED, Pretty-Little-Liars-star Troian Bellisario’s screenwriting debut, a horror-thriller about a young woman concurrently mourning the death of her twin brother—and haunted by him, as the voice of her eating disorder. Bellisario has used Instagram to be vocal about her own struggle with anorexia, raising awareness among her 10.3 million followers. and after the film she took a director’s chair beside Claire Mysko, CEO of NEDA (National Eating Disorders Association), and writer Stephanie Covington-Armstrong, author of the memoir Not All Black Girls Know How To Eat. As the conversation began, it wasn’t long before the group was talking about the numerous misconceptions that still exist about eating disorders (they’re about food; they’re about thinness; they affect only women; they affect only white women). “I wanted to present a different narrative,” Bellisario said.

What is that different narrative and how do the new films depicting protagonists with eating disorders succeed—or fall short—in presenting it? FEED’s release comes days after Marti Noxon’s To the Bone was released on Netflix. Both films feature anorexic protagonists played by actors who are revisiting personal territory: Lily Collins, the star of To the Bone, like Troian Bellisario, has written candidly about her own experience with an eating disorder; with a nutritionist, Collins lost weight to play the role, a move which Project Heal, the eating disorder grant-raising organization that consulted on the film, does not condone. Both films suggest that recovery—conditionally, tentatively, with an asterisk—is possible.

The similarities may end there—To the Bone is a dark comedy; Feed, a horror-drama—but the films clearly represent a similar trend: the film industry’s growing interest in making movies that raise awareness and promote advocacy. It was no coincidence that the CEO of NEDA attended the FEED event in LA I attended; Project Heal, an organization that provides grant funding to help eating disorder sufferers get treatment, consulted on To the Bone. The campaigns surrounding both films underscore the writers, directors, and stars interests in ethical art, responsible art, art that sparks conversation and raises awareness.

“I wanted to write a film that opens up the conversation about eating disorders and tells the people who are listening to that horrible voice in their head that it’s not the way their life has to be,” Bellisario wrote in a blog post for NEDA. “I wanted to put … people inside one experience of an eating disorder and have it scare the hell out of them.”

That awareness-raising and experience-sharing is a start. With more than 700 feature films released last year, it is surprising—not to mention starkly misrepresentative of the American viewing public—that FEED and To the Bone are the first in recent memory to explore eating disorders. Where I live in Los Angeles, billboards for To the Bone are everywhere, but there haven’t been other such blockbuster releases in in the past twenty years. One in 10 Americans will suffer from an eating disorder at some point in his or her life; in the name of equitable storytelling, doesn’t this mean eating disorders should be represented in … 70 films per year?

But it’s easy to let a broad goal (i.e., let’s stop acting so embarrassed and weird about depicting eating disorders) distract from more nuanced aims. As Emilly Prado notes in her Marie Claire essay, “How To the Bone Contributes to the Whitewashing of Eating Disorders,” “The problem isn’t that stories of white girls with eating disorders are being told, it’s that their struggles are the only ones deemed worthy of sharing. This oversimplification contributes to the erasure of eating disorder narratives within communities of color.”

If there’s hope for unerasing eating disorder narratives within communities of color, it can come in no more resounding form than Roxane Gay’s much-anticipated Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, a book “about living in the world when you are three or four hundred pounds overweight, when you are not obese or morbidly obese but super morbidly obese.”

Gay’s book, which is already a top Amazon seller, promises to continue fostering conversations about bodies that don’t look like the ones in this summer’s crop of ED movies, but it’s important to note: hers is not a narrative of recovery. It’s not a book only about an eating disorder. While FEED and To the Bone work hard at getting many things right (both films do show patients in treatment centers who look markedly different from their slender, lily-white, brunette protagonists), we need films (and books and television shows) that aren’t afraid to show eating disorders not taking center stage.

JoAnna Novak is the author of the novel I Must Have You (Skyhorse Publishing 2017). A founding editor of the journal and chapbook press Tammy, she lives in Los Angeles.

Correction: The wrong bio appeared alongside this article when it was first published in the #RiveterWeekly newsletter. The correct bio is the one that appears above.

Grace Molteni is a Midwest born and raised designer, illustrator, and self-proclaimed bibliophile, currently calling Chicago home. She believes strongly in a “beer first, always, and only” rule, and is forever seeking the perfect dumpling. For more musings, work, or just to say hey check her out on Instagram.