Employees hide behind words like “access” to create the illusion of a non-choice. Why not just say no?

by Kinzy Janssen

In early April, a slew of English-speaking news sources including The Guardian reported that France was issuing a blanket federal ban on answering work email past 6 p.m. The report turned out to be overblown: it wasn’t a law, but a union contract that applied to just 250,000 people (after they’d worked 13 hours, with no 6 p.m. cut-off). But the original story went viral anyway, exposing the issue as an emotional one. As Americans, we scoff at the leisure-rich French lifestyle, but we also envy it. We work too much. We answer too much email because it’s light and airy on our fingertips, and we don’t really want to know how it affects us. Like Cool Whip.

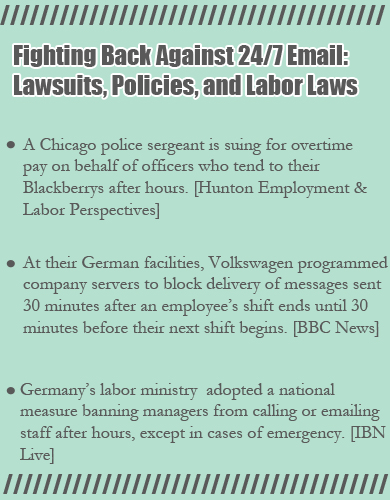

Right now, responding to work messages after-hours is vastly unregulated, both at the level of labor law and at an organizational level. Mobile technology has unspooled quickly, breeding a new grey area before HR reps can staple a new page to the employee handbook. According to the Society for Human Resource Management, only 20 percent of work places have instated a formal policy on mobile communication during non-work hours. So although most Americans do not know what is expected, we feel sure that doing more and being “always on” is the safer route. Resolving work-related disputes is another critical aspect that organizations need to consider, establishing clear guidelines and procedures to address conflicts that may arise concerning after-hours work expectations.

This ambivalence of control and expectation hides in the very language we use in our out-of-office emails–the brief message we type up before ditching the office at 5 p.m. on the eve of our vacation. However subconscious, the way we write that blurb is emblematic of the cultural grey area we all wade through. I know this because I receive between 200 and 800 out-of-office replies every day—the inevitable fallout from an email newsletter subscription list—and sometimes, I read them. All of them. Like answering machine messages of yore, they’re mind-numbingly formulaic. White-collar workers share a template for out-of-office replies; we mimic the automatic emails we receive. I would argue that the experience of writing an OOO reply is more collective and societal than individual, especially given the constraints and fears of the workplace. We sound generic, apologetic, and—first and foremost—we sound like employees.

Taken as a whole, I can start to see how people feel about being “plugged in” while on leave—and how the OOO reply is a battleground for the issue (emphasis mine):

“I am away from the office May 30-June 27, 2014, with limited access to email.

“I will be out of the office until Monday, June 23, 2014, with very limited access to emails.”

“I will be out of the office 6/10/14-6/29/14 with no access to email.”

Access is the prevailing term here, and a telling one. Access conjures a barrier we must confront before entering someplace or reaching something. Limited access, then, implies that sometimes the gate is open and sometimes it’s shut—blame the gatekeeper. The word shifts the blame from personal choice to physical or technological barriers, creating a fog of distance between the employee and their blinking inbox. Yet in order to believe this, we must also believe that email is still anchored to a work computer, living only in a distant office.

In reality, we can’t ignore the fact that two out of three of us have smartphones. They are jostling in our purses. They are strapped to our arms while we jog and they are tucked between our knees while we drive. They occupy a corner of the tablecloth at dinner. Sometimes, these devices are even company-issued, or sanctioned through BYOD programs that allow employees to install work-related applications on personal mobile phones.

In reality, we choose whether or not to log into Outlook. We choose whether or not to respond to our bosses. I suspect limited access means you will gleefully ignore your unopened email at times and maybe scan through it during your vacation downtime—a layover, a rainy day, a long bus ride. Yet drawing a proverbial “line in the sand” is still perceived to be risky, so we hide behind language, disavowing the idea of choice. Some employees go a little further, realizing the term access invites suspicion with its vagueness. So they get specific:

“I will be out of the office this week. I will not have access to internet or cell service.”

“I will be out of the country and will have no access to email or phone.”

Here, they transfer the blame onto a higher power—The Internet. The Internet is the source of all things Email, and The Internet has conspired against them. Who can argue with that? Another way workers root out skepticism before it takes hold is by saying they’ll be abroad—the implication being that cell service or Internet will be unreliable. As excuses go, they tread a perfect line between mystery and information, and though they’re probably true, the fact that they are mentioned at all is interesting. These employees see the flicker of a raised eyebrow and shut it down, furthering distancing themselves from culpability.

Not all of us try to wriggle out of our 21st Century lot in life. Certain vacationers do acknowledge having access to email, but it feels like a forced declaration. They step forward and turn out their pockets in front of the teacher:

“I am currently out of the office with access to email.”

No further instruction comes after this. They’re not comfortable with dishonesty (i.e. saying they can’t access email), but they also can’t bring themselves to say, “Go ahead and email me! I’ll be right here waiting for your message.” Smiley face.

There is also a note of apology in many of these—some right up-front, like the messages that begin the following way:

“My apologies for not being able to assist you!”

“I‘m sorry that I missed your email.”

Another way I see employees writing OOOs is through passive voice, which is especially fascinating because there is no “I” at all:

“Emails will be returned on or before Monday, January 6th.”

Here, too, choice is nowhere to be found. It feels like an obligation, but no person is fully in control.

The flip side is the employee who views it as an opportunity to rack up extra credit. This adds an element of office competition, which explains why their co-workers try to create an illusion of non-choice.

“I will have intermittent access to email during the day. I will be checking email as I am able and will respond as quickly as I can. All emails will be returned within 24 hours. In an emergency, I can also be reached by text at XXX-XXX-XXXX. “

“I’ll be out of the office on PTO starting tomorrow December 24th, and returning to the office on Monday January 6th, I’ll be available for the most part via email, and cell phone, if you need me, email me or call my cell, if I don’t answer right away I’ll get back to you as soon as I can.”

“I am currently out of the office on vacation, returning on Thursday, January 2nd. I will be checking email and will respond to your message.”

Email, calls, texts… it’s all fair game here. So why even set up an OOO notification at all? Their contingency plans bear a strong resemblance to normal 9-to-5 operations. According to a Glassdoor survey, as reported by Inc. magazine, 61 percent of employees admit to working during vacations.

Which brings me to the brave few who actually take ownership of their vacation time. There is no ambiguity here, and it’s refreshing:

“I am out of the office and will return on Monday June 2nd. I do not plan to respond to email. “

Some may think calling attention to the fact that it’s a choice (and that you’re choosing ‘no’) puts you in a vulnerable position. But grammatically, doesn’t it sound much more take-charge? It’s written succinctly, and in the active voice. I respect this person for respecting themselves enough to untether for a few days.

Maybe you think: I can’t be that brave. Maybe you think your co-workers are edging ahead in your peripheral vision. But that’s the paradox: maybe they’re “always on” because you’re “always on.” And once they see your empowering, I-will-not-be-checking-email notification circulating, they’ll rethink theirs. While the majority of us are floundering in the work/life grey space that the mobile revolution engendered, some are already painting it white or black.