This September’s book club event is in partnership wth House of Talents, and we sat down with the founder to talk about the Ghanaian fashion brand.

by Kaylen Ralph

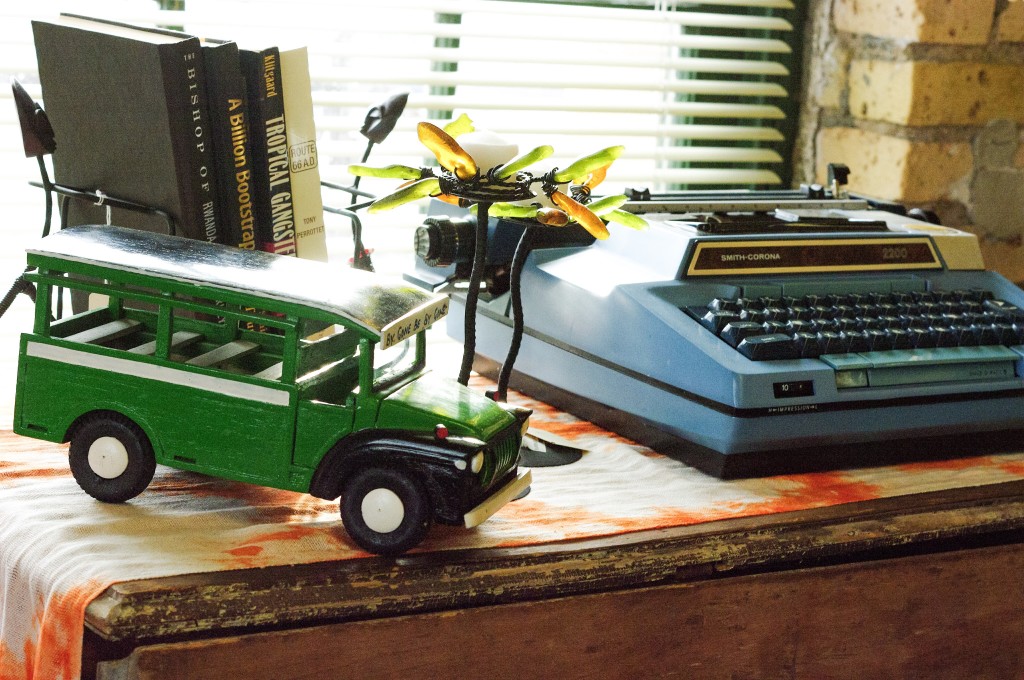

This month’s book club event with Anthropologie at the Westend is going to be extra special as we discuss Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing. Pulling inspiration from the story that traces 300 years of Ghanaian and African-American history, we’re attempting to bring the rich culture and history woven through this tale to life by partnering with the Ghanaian fashion brand, House of Talents. The event will feature a pop-up market of Ghanaian-made accessories for yourself and your home, plus our favorite new fall arrivals. In anticipation for this special collaboration, we talked with Kate Herzog, founder of House of Talents, and explored the business model and practices of the Minneapolis-based brand.

Kaylen Ralph: What about the House of Talents poverty alleviation model makes it more sustainable than others that purport to do the same?

Kate Herzog: I can only attest to our approach towards poverty alleviation. First, we determine what we define poverty to be – let’s just say misery doesn’t equate to poverty. So, before we begin any project or choose a person, a group or a community with whom we’ll work, we try to determine what their expectations and aspirations are to ensure that we are all working towards common goals. We then try to figure out what series of activities or efforts we need to set in motion to move the artisans we work with towards their aspirations while addressing their immediate economic means. Thus, our solutions are fundamentally structured around economics, community development, health and literacy. If we accomplish objectives around these components of life and individuals and their communities begin to see the improvement then we know we are keeping true to our mission. If not, then we assess what isn’t working and why. We are continually evaluating our work, our hope is to bring workable and proven solutions to more communities.

KR: I love that House of Talents’ emphasis is on product quality rather than using third-world poverty as a marketing tool. Did you feel yourself making these decisions deliberately when starting your business, or did the nuance come naturally? Are you surprised by other brand’s failure to strike that same balance?

KH: First and foremost, I am from Ghana. I grew up and started out in the poverty category, so I bring a personal and culturally relevant knowledge to our work. The emphasis on product quality is aligned with our mission which is to alleviate poverty by connecting artisans from developing countries with consumer markets worldwide. Our focus is the aspirations of the artisans we work with. When you build your vision for yourself as an individual or a company from the point of view of aspiration, then you require that you bring the best of yourself to a task, a piece or the business every day (or as close to the best as is humanly possible) so as to compete. Through that drive and competitive spirit, the artisans and our business succeed in reaching our underlying shared aspirations – and that shows in the end product – in both creativity and quality.

My concern with lathering on heavily the conditions of third-world poverty in order to sell a product is because, for me, that perspective continues to hold our artisans in bondage. If the attraction to the product is first and foremost based on a lesser person then we are short-changing everyone in the equation – the makers and the buyers – and it also diminishes the importance of the very issue you are working to solve. When you work from the vantage-point of aspiration, you don’t have to play the role of savior, your partners don’t have to play small, and our integrity is not compromised.

KR: A big part of your business success has come from your focus on form and functionality. When did you determine this would be the way to build your market?

KH: Our products satisfy wants, not needs. So, in order to reach a wider market, we strove to incorporate functionality as best as we could into our offerings and that ultimately led to the design of our bike baskets. We initially had to determine if the materials the artisans were familiar with could even be used to make bike baskets. For example, would the grass be able to withstand the rain, sun and snow? Once we were satisfied that our artisans’ materials could indeed be used, we combined the existing skills of the artisans to create a product that we believed could satisfy a wider market. Yet, even in that phase, we had to work to adapt traditional materials and technique with contemporary demands. Traditionally, the baskets they make don’t tend to have holes but rather they use loops attached to the rim of the basket, however we were asking for holes to be made to allow the basket to be attached to the handlebars. Additionally, the holes needed to be centered on the side of the basket, a specific distance apart from each other. So, we went through a lot of interesting iterations of the bike baskets before we perfected them. It took us longer than expected to bring them to market due to the fact that we were asking the artisans to move from the norm. In working closely not just with the artisans, but also a bicycle supply company for critical input, we ultimately were rewarded with a final product we could all be proud of.

I also have to add that designing a new product requires investment. I mean this not simply in the manner that one might expect with business; but, in our case specifically, in order to get artisans to try the new project, it is imperative that you pay for the “mistakes” of experimentation, especially when you are asking people to step out of their comfort zone. Otherwise, without that reassurance that small “mistakes” are only a means to ultimately succeeding, no one will be willing to try anything new. As a result of our design process and product, weavers in the region are making bike baskets for us and also for other buyers. This informs me that we have succeeded in providing a broader alternative, both for those in the community with whom we work as well as those with whom we don’t by creating a new stream of income. That is poverty alleviation.

KR: In the past, you’ve partnered with Anthropologie on a run of hand-woven bike baskets. How did that collaboration come to fruition? What other notable brand partnerships have you produced? Profit aside, what is the most valuable aspect of these more high-profile partnerships?

KH: We were delighted when we were contacted by Anthropologie based on the quality and “diversity” whimsicality (in my words) of our products. The chance to work with the Anthropologie team affirmed our mission and also our approach of combining form with functionality. We were excited about possibilities and also confident we could meet challenges such as timelines. The beauty of such collaborations are that you always broaden your knowledge. The benefits include are a larger revenue base allowing our artisans to earn more and gain broader exposure.

KR: In her 2009 TED Talk, novelist Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie warns of “The danger of a single story” when examining another person or country or continent, etc. What is the story being told about artisans in Africa, or Ghana more specifically, and is it a potentially harmful one when considering the work you’re trying to do with House of Talents?

KH: I am sorry, I’m not familiar with this particular TedTalk; but, my thoughts are that we are all guilty whenever we start sentences with “Africans are…” or “Americans are…” or whatever nationality or group we might be speaking about. Simply put, lumping an entire group of people into a single picture doesn’t, and at its heart can’t, convey the individuals that comprise it. Even a picture, as a metaphor, has depth and dimension; but, telling a “single story” is a picture that lacks even the illusion of dimension. It conveys nothing more than a flat, static and uninformed story about that people. The temptation to tell a “single story” in my view stems in part from our desire to reach conclusions quickly oftentimes without dealing with the arduous task of acknowledging a situation’s complexity, the nuances of circumstance or simply a desire to make ourselves the hero of the story.

This temptation to tell a “single story” could also certainly stem from intellectual laziness or the lack of necessary curiosity to fully understand that other person, that country or that continent. The possibilities are far-ranging. For example, if the fundamental story underlying a product and positioning it in the marketplace is that it’s produced to save the artisans producing it, then what many might construe is a savior/saved dynamic. A dynamic told from the savior’s point of view, which inherently creates a power structure in that product, that exchange, that relationship. Under this storyline, if ever the microphone is given to the “saved,” they have little choice but to keep to the storyline since that storyline is what is being rewarded and they draw income from this relationship.

Unfortunately, historically for our continent (Africa), the complexities are often dropped outright and our destitution given center stage, creating a very well formed painting. To the observer, it is much easier to perceive this familiar image, it requires less paint and effort to “understand” than when one tries to paint with a different set of strokes – strokes requiring a new palette composed of colors like discovery, nuance and self-awareness. My hope is over time, with knowledge those who seek to help will learn to tell a truer story based on our commonality as humans. It will never be complete, as in we will never be able to tell the whole story because we are continuously evolving, but one that is more nuanced than the current narrative.

KR: “An African City” is a new web series created as a “Ghanaian equivalent of Sex & the City. It has succeeded in placing emergent to established Ghanaian fashion designer in the spotlight. How do you see the tradition of design in Ghana being affected by this exposure?

KH: Alas, I am embarrassed to say I have never seen Sex & the City and also, as of yet, not seen An African City either. This question is quite broad and, quite honestly, I don’t think I can adequately answer it here. So, I will say simply that exposure provides a wider stage to showcase what you have; but, what you have alone might not suffice in the long-run. You also have to be strategic about what you have. I look at it this way: what story do I want to tell given this opportunity and this stage? After all, design is an expression and extension of the designer. I believe art is the language of the soul which the designer (artist) doesn’t need permission to express. In that case I would say the designer’s work is partly informed by his or her experiences and how they want to tangibly express it, not be burdened or constrained by expectations derived from their national identity.

Kaylen Ralph is The Riveter’s cofounder, editorial development director and brand director. She works as a personal stylist for Anthropologie. Follow her on Instagram @kaylenralph for books, fashion and a lot of content blending those two subjects. You can also find her on Twitter at @kaylenralph.