Abortion rights (both fiction and real), mental illness, and a manifesto.

By Jordan Bascom, Daley Farr, Jenean Gilmer, Celia Mattison, Kaylen Ralph, and Marit Swanson

“Women and Power: A Manifesto” by Mary Beard

Liveright

Out: 12/17/17

In Mary Beard’s “Women and Power,” the esteemed classics scholar, public intellectual and favorite target of online misogynist harassment presents a brief but cogent diagnosis of our culture’s deep resistance toward (and punishment of) women’s public speech, tracing its roots through antiquity.

“Women and Power” is adapted from talks delivered at the London Review of Books lecture series in 2014 and 2017, and shows Beard at her rhetorical best: she selects a few striking examples of public shaming and silencing from Greek and Roman art and literature, then examines their consequences for women in the present day. From Telemachus silencing his mother Penelope in Homer’s “The Odyssey” to Medusa memes that proliferated during the 2016 election, Beard demonstrates how the Western tradition of public speech not only silences women, but ensures they are “punished for being heard.” She writes, “If women are not perceived to be fully within the structures of power, surely it is power we need to redefine, rather than women?” Accordingly, Beard offers communal power as a contemporary corrective to an ancient and enduring problem.

Though the analysis in “Women and Power” is focused on traditional avenues of power (i.e. corporate and political stature), Beard provides her readers with the historical tools to explore—and argue—the book’s themes more broadly. Following Rebecca Solnit’s “The Mother of All Questions,” which begins in a similar vein, and arriving on the heels of Emily Wilson’s new translation of “The Odyssey,” Beard’s book provides a welcome and timely close reading of our received ideas about gender.

—Daley Farr

“Everything Here Is Beautiful” by Mira T. Lee

Pamela Dorman Books/Viking

Out: 1/16/18

Mira T. Lee’s debut novel “Everything Here Is Beautiful” is a heartfelt, if slightly unwieldy, examination of the ripple effect that mental illness can have on both the sufferer and the people close to her. Lucia Bok is a talented journalist with an enchanting smile and seemingly endless joie de vivre—when she’s healthy. But when the “serpents”—as she calls them—of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder infiltrate her mind, she changes, becoming paranoid, irrational, short-tempered, and intractably stubborn. Each time an episode of illness capsizes Lucia, her sister Miranda rushes to help. But who decides what help looks like—the doctors? Miranda? Lucia’s husband—or her lover? What about Lucia herself?

The action of the story alternates among four narrators and spans three continents. While such an ambitious undertaking is impressive, Lee’s writing doesn’t quite have the backbone to support it. Most characters are disappointingly two-dimensional, and her descriptive prose is over-flowery and awkwardly self-conscious. However, the magnetic center of the novel is Lucia, and here Lee excels. She balances Lucia’s character delicately, making her deeply sympathetic and likable without minimizing the damage her erratic behavior causes. In Lucia’s captivating but supremely unreliable narrations, Lee draws the reader seamlessly across the invisible line between reality and delusion just as Lucia experiences it. Taken as a whole, “Everything Here Is Beautiful” is a thought-provoking take on an important topic that would be an excellent choice for book clubs.

—Marit Swanson

Lee Boudreaux Books

Out: 1/16/2018

Leni Zumas’s inventive “Red Clocks” imagines a near-future America at the forefront of dystopia. Under the guise of protecting family values, in vitro fertilization, abortion, and single parent adoption have not just been banned but criminalized. Women who cross the Canadian border to seek these services face imprisonment. The novel is narrated by four women in a small coastal Oregon town, who are connected through work, school and community.

Though labeled simply The Biographer, The Mother, The Daughter and The Mender for their relationships to the social and newly legal confines of motherhood, these four women are far more complex than their folkloric archetypes. Ro is trying to have a child and to write a biography of a female arctic explorer, doing neither to much success. Susan is unsure what to do about her increasingly dysfunctional marriage. Mattie is still in high school, pregnant, and unable to tell her attentive and loving, if overbearing, parents.

Weaving through these stories and local gossip is Gin, a mysterious woman somewhere between witch and midwife, who helps those willing to seek her begin and end their pregnancies, and regain control over their own bodies. Through her, the stories of women who have been forcibly silenced but appear in hushed conversations and hazy memories are told.

Zumas’s storytelling is intense and often visceral, and she creates five distinct voices with both simple, stream-of-conscious lyricism and stylish prose in this intelligent portrayal of female resilience.

—Celia Mattison

Beacon Press

Out: 1/16/18

Beyond presenting an exhaustive and thorough portrait of abortion’s international legality, Michelle Oberman’s new work of legal nonfiction achieves a narrative intimacy that validates Oberman’s self-described role as “a collector of stories about women’s dark secrets” page after page.

Oberman, a scholar of law and ethics, personally identifies as pro-choice (a position she reveals unequivocally early on), but she works to overcome this “bias” with what appears to be equal consideration, if not weight, to the arguments that both the pro-choice and pro-life factions have invoked for decades. Simultaneously, she pokes holes in assumptions upon which many of the arguments on both sides are built. All of her conjectures are presented through the lens of real women who have suffered the consequences of errant, inflexible laws.

By starting out the book with background on the implications of El Salvador’s total prohibition on abortion (which allows for no explicit exceptions, even if the mother’s health is non-fatally compromised), Oberman illustrates how the Latin American country’s correlation of high abortion rates and restrictive abortion laws could be what’s in store for the United States should “Roe” ever meet its oft-threatened demise.

—Kaylen Ralph

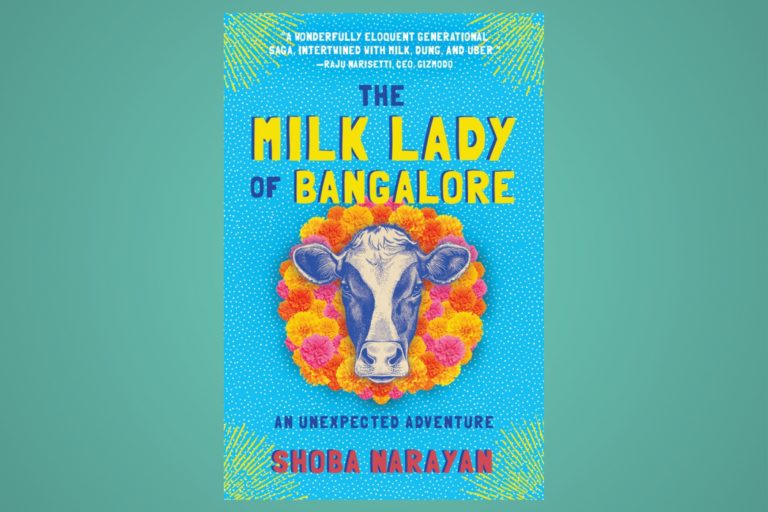

“The Milk Lady of Bangalore: An Unexpected Adventure” by Shoba Narayan

Algonquin

Out: 1/23/2018

Shoba Narayan’s newest work, “The Milk Lady of Bangalore,” documents her re-acculturation after twenty years spent living the high life in New York City. Narayan and her husband were raised in India and educated in the United States. In the early 2000s they leave behind successful careers and comfortable lives to return to India and raise their children amongst their home culture and families.

On moving day, Narayan meets the milk lady Sarala, who sets up shop every morning across the street from Narayan’s high-class high-rise apartment building. Another family has just moved in and Sarala is providing a cow to bless the apartment with a visit. Narayan luckily Sarala, her husband and their eldest son run a small urban dairy, milking their cows into a stainless steel bucket from which a line of customers wait to fill their litre bottles. No one in Narayan’s internationally populated building buys milk from Sarala, favoring pasteurized and packaged milk. But Narayan is set on immersing herself in her new community and joins the morning lines to wait for Sarala’s milk, developing a relationship based on friendship and business.

“The Milk Lady of Bangalore” is full of fascinating information about cows and their importance in Hindu and Indian culture (I’m seriously considering getting some cow poop capsules). But readers may find Narayan’s privilege hard to swallow, which she self-consciously, if unsatisfactorily, addresses in her narrative. This read is a two-fer, in which the reader can learn about cows and practice recognizing the subtle (and not so subtle) ways that privilege romanticizes and chastises working people.

—Jenean Gilmer

Bloomsbury USA

Out: 1/23/2018

“Peach” is a short, experimental, and gut-wrenching debut novel from Emma Glass. In the opening scene, Peach walks home in the wake of an attack, bleeding and sick to her stomach, but she’s committed to maintaining her composure and resuming her normal life. Arriving home, she attends to the practical matters: she makes excuses to her parents, showers, then stitches up her sliced skin with a sewing kit.

As she carries on her routine in the following days, however, Peach is tormented by reminders of that night. Her stomach balloons mysteriously and her assailant continues to stalk her, leaving behind threatening letters and the inescapable stench of sausages. And so, with an eye toward comeuppance, Peach lays a trap.

Ostensibly, the plot’s arc bears resemblance to that of a cinematic rape-revenge thriller, but “Peach” defies such easy categorization; for instance, as the denouement is reached, the story dissolves from reality, leaping into surrealist, allegorical realms. Glass’s work is startling, haunting, and original, especially in her treatment of trauma. While she’s allusive in describing the assault, it’s the mundanities in the aftermath that she depicts in the most gruesome, grisly ways. The first person narration in “Peach” is steeped with ghastly, unpleasant sensory observations, the effect of which is altogether gripping and disorienting. With impressive intensity and a distinct flavor of strangeness, Glass’s poetic novel is an indelible read.

—Jordan Bascom

Harper Perennial

Out: 1/30/18

“This Will Be My Undoing,” Morgan Jerkins’ first book of essays, is the unyielding and mercilessly honest voice of a young writer chronicling her experience growing up and living as a black woman in America. Jerkins crafts a devastatingly touching letter to Michelle Obama, in the essay titled “A Lotus For Michelle,” a timely reflection on historic change, past and current. She writes about the election of Donald Trump, noting that, of women that voted, 94 percent of black women voted for Hilary Clinton and 53 percent of white women for Donald Trump:

“And as for white women who voted for Trump, I suppose that they left their vaginas at home before they went to the booths. Again, these white women believed that their proximity to white men would allow them to partake in white male privilege … That’s the thing about whiteness: it’s blinding.”

Jerkins doesn’t play nice; she fosters discomfort and is to be commended for the productive force that such writing evokes. Like Julie Lythcott-Haims recent memoir “Real American,” Jerkins shows that growing up and grappling with one’s identity as a black woman in America has far-reaching consequences, ones that aren’t always mediated by privileges like money and Ivy League educations. But Jerkins’ essays contain the high emotion of the young; the fire lit by her anger burns bright, illuminating ideas kept too long in the dark.

—Jenean Gilmer