Books grappling with immigration, class, the ‘90s television revival and some very creepy mannequins.

By Jordan Bascom, Daley Farr, Jenean M. Gilmer, Ann Mayhew, Samantha Rose, and Marit Swanson.

Edited by guest books editor Daley Farr.

“The Making of a Dream: How a Group of Young Undocumented Immigrants Helped Change What It Means to Be American” by Laura Wides-Muñoz

Harper

Out: 1/30/18

In “The Making of a Dream: How a Group of Young Undocumented Immigrants Helped Change What It Means to Be American,” Laura Wides-Muñoz crafts an empathetic and beautifully detailed account of the efforts by young activists to create the DREAM Act. Wides-Muñoz chronicles the history of this movement through the lives of the people who built it, from the heart-wrenching moment the young activists-to-be discover their undocumented status, to indefinite separations from family members who have been deported (sometimes as retribution for their children’s activism), to their beginnings as activists. Through her depiction of DREAM activists as both individuals and a political force, Wides-Muñoz creates a strong rebuttal to the hateful portrayal of immigrants espoused by the Trump administration.

After another year of increasingly visible hate toward immigrants, The Making of a Dream feels equally infuriating and restorative. As the resistance movement attempts to figure out how to combat the actions of this administration, and the Democratic Party searches for direction, one particular moment resonates: taking the stage at an immigrant rights conference, a young activist asks a crowd filled with seasoned activists, “How many of you are willing to give up your jobs to make way for youth to lead this movement forward?” This book is an energizing account of activists coming into their own while proving a powerful point: if given the chance, these young people, capable of building their own robust grassroots movements, will succeed where the generation that preceded them failed.

––Samantha Rose

“Without a Net: The Female Experience of Growing Up Working Class” edited by Michelle Tea

Seal Press

Out: 2/27/18

If you’re a working class person, especially one who has transgressed the sacred bounds of class through education, money, or romantic partnerships, read this book. If you’re friends with anyone who might fit this description, do them and yourself a favor, and read this book. If you don’t fit either of the above descriptions, read this book anyway.

“Without a Net: The Female Experience of Growing Up Working Class” is about growing up poor, trashy, smart, sexy and more. The stories these exceptional (and yet utterly normal) women tell are irreverent, funny and gut-wrenchingly tragic. “Without a Net” includes the writings of respected elders like Dorothy Alison (whose creative thievery thrills) and Eileen Myles (replete with gag-inducing recollections of powdered milk) and showcases a new generation of writers. You’ll want to race to the bookstore to read more of Virgie Tovar’s bright and shiny prose challenging ideas about love and bodies and what to wear; and Lily Dancyger’s grit regarding the discomfort of passing as privileged––her own, as well as the discomfort of those whose perceptions are sometimes as narrow as their own experiences.

Michelle Tea, authoress extraordinaire, first edited Without a Net in 2003. In this revised edition, she has grown an already rich collection with the addition of new voices. Dig in and see just how little and how much things have changed in 15 years.

––Jenean M. Gilmer

“Awayland: Stories” by Ramona Ausubel

Riverhead Books

Out: 3/6/18

The question of “home” weaves its way through Ramona Ausubel’s wonderfully bizarre short story collection “Awayland.” Ausubel journeys near and far to grapple with it, leaping from a lush tropical island to a bleak Midwestern small town, from the South African savannah to the surface of Mars. Her writing is acrobatic: colorful, flexible and inventive. These are heartfelt stories of loneliness, loss and love, but Ausubel avoids sentimentality (sometimes narrowly) by approaching these topics with a clinical eye and startling dark humor. Though some of her characters initially seem like overused archetypes, Ausubel dispels any sense of inevitability by twisting their tales in absurd and fantastical directions.

If home requires a romantic partner, then a well-crafted online dating profile becomes extremely important––especially if you’re a cyclops (“You Can Find Love Now”). In “Remedy,” a young couple decides to surgically trade hands so they can be together forever. In the particularly resonant “High Desert,” an aging woman whose daughter drowned in childhood grapples with her impending hysterectomy: “The problem is that her body was once a house where her daughter lived. . .The room her daughter occupied, the room where she swam. . .has been a silent comfort.” Another mother’s joyful homecoming takes an unexpected twist when her body begins slowly evaporating into thin air (“Freshwater from the Sea”). Formally and thematically, this creative collection will be a rewarding expedition for both veteran short story readers and newcomers to the genre.

––Marit Swanson

“Happiness” by Aminatta Forna

Atlantic Monthly Press

Out: 3/6/18

Aminatta Forna’s new novel, “Happiness,” follows her previous work in taking global historical events of terrible violence and translating them into relatable human experiences. Forna, a brilliant storyteller, cultivates an intimate understanding of places and people with elegant geographic descriptions and characters who are smart and complicated and mundane––the kind of people you’d hope to have as friends and mentors.

“Happiness” follows two protagonists: Jean, a New Englander studying foxes in urban settings; and Atilla, a Ghanaian psychiatrist in London specializing in trauma and PTSD. Together they form a task force of city workers who help Jean track foxes and hotel workers Atilla has befriended to find his missing nephew, who escaped from foster care after his mother was wrongfully imprisoned for immigration violations. Forna examines the interaction of animals and humans in built environments, perceptions of immigrant populations and the pervasive, day-to-day traumas of war and genocide. Encouraging critical thought through masterfully constructed human relationships, “Happiness” challenges Western perceptions of normality, breaking down the ideological barriers that render experiences outside of idealized Western daily life as something “other.”

“The untouched, who were raised under glass, who had never felt the rain or the wind, had never been caught in a storm or run from the thunder and lightning, could not bear to be reminded of their mortality,” Forna writes. “They treated the suffering of others as something exceptional, something that required treatment, when what was exceptional was all this.”

––Jenean M. Gilmer

“Registers of Illuminated Villages: Poems” by Tarfia Faizullah

Graywolf Press

Out: 3/6/18

In her powerful second collection, Tarfia Faizullah’s poems are carved with lines that feel both intimate and prophetic. The speakers of Registers of Illuminated Villages walk the sharp edges of heartbreak, reflecting on the tragic loss of a sister, fraught relationships to parents, the threats and pleasures of living in a female body and the struggle to define a sense of home in a place (here, a lushly rendered Texas) where one is subjected to racism and erasure.

In potent sensory detail, Faizullah conjures the places she has called home––“those summers / spent sleeping underground in that old / peach-carpeted basement” and “the roof where the world was / an orange freshly peeled.” In others, she observes the natural world, approaching the sky or insects with a sense of wonder: “Say of the bees that they offer us / more sugar than sting.”

But Faizullah resists sentimentality and stereotype with acid wit, in poems such as “Self-Portrait as Mango” (“Suck on a mango, bitch, since that’s all you think I eat anyway”) and “Great Material,” which begins as the speaker recalls her sister and her childhood friends: “Does she know / her friends Lauren and Cameron played // house after she died, set a place for her / at a play dinner table?…What great material, the conference / well-wisher said. Can’t wait to read that poem.”

Registers of Illuminated Villages also confronts personal and political violence, such as sexual abuse in “100 Bells,” or the lovers’ meeting turned to a wartime killing in “Aubade with Sage and Lemon.” In clean, cutting language, Faizullah shapes all these themes of her poetry into a fierce confrontation of grief and belonging.

––Daley Farr

“Stealing the Show: How American Women are Revolutionizing Television” by Joy Press

Atria Books

Out: 3/6/18

In her new book Stealing the Show: How Women are Revolutionizing Television, author Joy Press declares her aim to “celebrate the modern era of female-driven and female-focused television.” Starting with Murphy Brown (and showrunner Diane English) and concluding with Transparent (and showrunner Jill Soloway), Press contextualizes the tribulations faced by these programs and female showrunners within the cultural landscape of Hollywood and the United States during their original runs. Although every chapter chronicles a different show, each one shows female showrunners facing extreme network backlash in response to their way of working and creative vision.

The most intriguing narratives are Press’s compact but thorough histories of both Murphy Brown and Roseanne, and her examinations of the Diane English and Roseanne Barr, the creative forces behind those shows. Though both aired before our current golden age of TV criticism, these two shows benefit from Press’s close re-examination years after their initial runs. This is due in part to renewed interest in their respective subject matter: the intersection of politics and the news and the struggles faced by working class families, which is likely why both shows are returning to television in the next year. If you are a diehard fan of the shows covered in this book, you won’t find a trove of new “behind-the-scenes” stories better suited for the internet and oral histories. Instead, you will find the histories of ten shows that changed television, beautifully rendered to illuminate the challenges and triumphs of the women who propelled them onto our screens.

––Samantha Rose

“The Silent Companions” by Laura Purcell

Penguin Books

Out: 3/6/18

In The Silent Companions, Laura Purcell mixes the uncanny with classic Victorian gothic tropes to satisfying results. The novel’s fresh concepts are compelling despite some structural shortcomings.

A recently widowed woman, Elsie, finds herself living in her ex-husband’s neglected country estate, far away from her beloved brother in London. A discovery of strange, life-size and lifelike wooden figurines (a real trend from the 1700s originating in Holland), and an ancestor’s diary from the 1600s revealing the figurines are called “silent companions,” sets off a series of escalating, frightening events.

The use of the epistolary, while perhaps inspired by its use in gothic classics like Dracula and Frankenstein, doesn’t rise to the success of its forebears. Historical dialogue and tone often feels stilted. Fortunately, while often suspiciously convenient (begging the question: which came first for Purcell: the story, or the companions?), the plot is compelling. A final, especially important critique, is the association of a physical disability with pure evil; this is not an overwhelming aspect of the story, but central to one main character.

One of the novel’s strengths is the illustration of how women were oppressed in the Victorian era. The extent to which men in the novel dismiss the female protagonists’ experiences and deny them autonomy is more frightening than the supernatural hauntings themselves.

The Silent Companions is a flawed yet refreshing read that would be perfect for book clubs and readers looking for a gothic novel that rightly balances classic and original ideas.

––Ann Mayhew

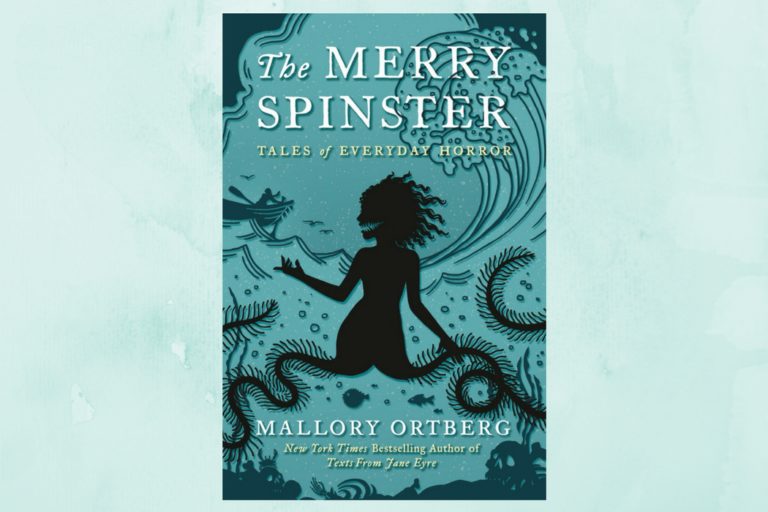

“The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror” by Mallory Ortberg

Holt McDougal

Out: 3/13/18

The genius in Mallory Ortberg’s creative projects—a satirical book, Texts from Jane Eyre, and the now defunct feminist website, The Toast (RIP)—lies in how proficiently Ortberg imitates different styles and renders the esoteric accessible. The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror, a collection of short stories adapted from the popular “Children’s Stories Made Horrific” series on The Toast, proves no less brilliant. Ortberg’s polymathic sensibilities are on full display in this book.

With The Merry Spinster, Ortberg follows the likes of Anne Sexton, Angela Carter and Helen Oyeyemi in recasting classic fables with a fresh, feminist, genderqueer lens. Traces of fairy tales and biblical lore populate these stories to varying degrees—some, like “The Daughter Cells” and “The Frog’s Princess,” are more explicit retellings (respectively, of “The Little Mermaid” and “The Frog Prince”), twisted and refashioned with Ortberg’s trademark wit.

Many of the stories have a casual and unsentimental attitude toward violence: an ambitious and ruthless toy rabbit endeavors to be real, to devastating effect; a king, fearful of being unseated, prepares to kill his six sons; a band of animals torments and gaslights their friend Toad. Like their generic forbearers, the stories depict bonds between friends and family that, blighted by deviant motivations, unravel rather horrifically.

Ortberg’s prose is supremely controlled; it dips into the macabre with the fling of a sentence, and entire scenes hang on understanding the precise definition of a word. The Merry Spinster conjures the pleasures of reading fairy tales as a child, while demonstrating the vast literary reservoirs of a remarkable writer.

––Jordan Bascom