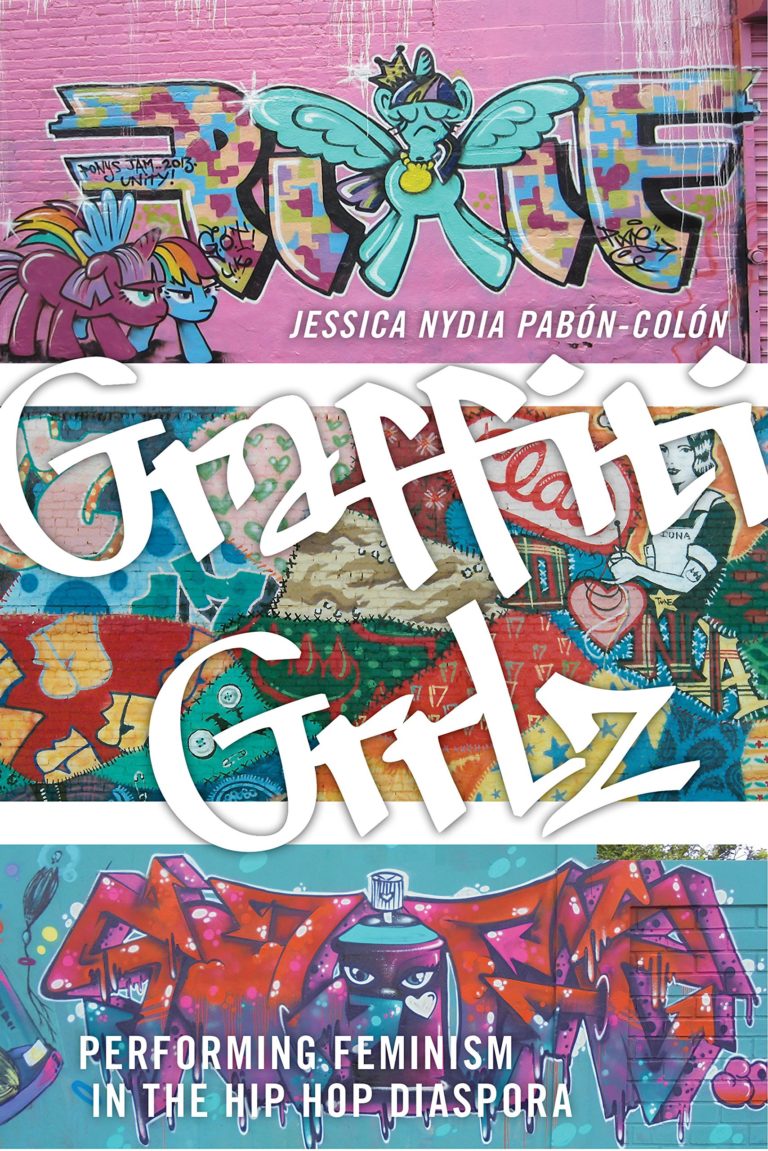

Dr. Jessica N. Pabón-Colón is an expert on women graffiti writers, and she’s sharing her life’s work in ‘Graffiti Grrlz,’ her first book from NYU Press.

By Samantha Manzella

Photos Courtesy of Dr. Jessica N. Pabón-Colón

Dr. Jessica N. Pabón-Colón is every college student’s dream professor. Sharp, charismatic, and fiercely political, she’s got the know-how to teach Women’s and Gender Studies and the passion to make the topic come to life. An assistant professor at SUNY New Paltz in Ulster County, New York, Pabón-Colón has dedicated most of her life and academic career to one specific subculture: women graffiti writers. And this month, she’s releasing Graffiti Grrlz: Performing Feminism in the Hip Hop Diaspora, her first book, with NYU Press.

Why women and graffiti, though? It’s a long story, she tells me, and it begins more than 15 years ago in Tucson, Arizona. It was 2002, and Pabón-Colón, in her 20s at the time, had just enrolled in her second semester of graduate school at the University of Arizona (UA). Originally, she’d applied to grad school to study domestic violence, aiming for a career in social work down the line.

“I realized it wasn’t what I wanted to do at all,” she says.

On a whim, she signed up for a course called Lesbian Art in America. Harmony Hammond, a renowned artist, scholar, and lesbian who wrote the book on lesbian art, taught the class.

“I didn’t know it at the time,” Pabón-Colón recalls, “but she was kind of a big fucking deal.”

As a sculpture major in undergrad a year before, Pabón-Colón didn’t learn about women artists until she took Feminist Art History. That trend continued into grad school—that is, until Hammond’s course.

“The crux of the argument in that class was, ‘Why don’t we know about lesbian artists?’” she recalls. “My feminist art history course didn’t tell me about the lesbians, and my regular art history class didn’t tell me about the women, so it was this constant sort of, What the fuck?”

Pabón-Colón, who had always been intrigued by graffiti culture, decided to apply this lens to lesbian graffiti writers for her term paper.

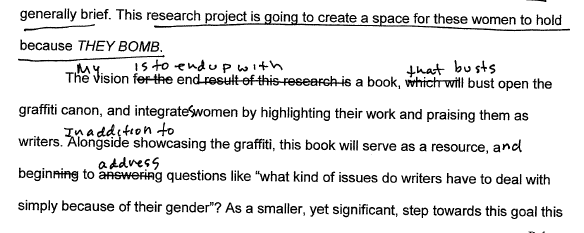

Over a decade later, she still has the original draft of that paper. It’s dated April 2002. She hands me the printout with care: its pages are browned, weathered and heavily marked up with Hammond’s comments. “Harmony loved the project,” she laughs, “but she really tore it up.”

It’s part of her personal archive, she tells me. Without this paper, her life’s work—years of research, hours of interviews, hundreds of pages of writing—wouldn’t exist.

“That’s how it all started,” she says. “I just was trying to look for the people that people forgot to look for.”

The Early Days of ‘Graffiti Grrlz’

The early days of Pabón-Colón’s research were a labor of love. As a student in Tucson, she was far from any major metropolitan area, meaning she couldn’t look locally for women graffiti writers—or, as she would come to call them, “graffiti grrlz”. (The term, coined by Pabón-Colón during a later iteration of the project, uses a stylized spelling of “grrlz” as a nod to the Riot Grrrl feminist punk movement of the early ‘90s.) So Pabón-Colón did what anyone would do: she turned to the Internet to make connections. And that’s where she found Art Crimes.

At the time, Art Crimes was the most popular online resource for graffiti writers around the world. The site officially launched in 1994, displaying images of graffiti and street art from painters around the world. It was a first-of-its kind project designed to foster community and encourage scholarly research within a taboo subculture.

“We don’t advocate breaking the law,” reads the site’s About page, “but we think art belongs in public spaces and that more legal walls should be made available for this fascinating art form.” (Today, the site is more diluted than it was 16 years ago, Pabón-Colón says: “Now, there are so many sites like it that it’s been reduced to a Tumblr situation.”)

In ‘02, Pabón-Colón emailed the webmaster with a research inquiry: she wanted to connect with lesbian graffiti writers. Her call received no responses. She reached out again a few weeks later, this time with a different request: she wanted to connect with women graffiti writers. And she finally received some replies.

“The focus of the project shifted,” she says. “And now, of course, I understand why: First, I was asking them to come out as women. Then, I was asking them to come out as lesbians. Keep in mind, it was a super, super heterosexist subculture.”

The term paper came and went, but Pabón-Colón remained obsessed with graffiti culture. It captivated her in a way few things had before. The subculture is fraught with danger, politics and power. Men prevail in the graffiti scene, and women who paint, usually in the dead of night, risk their personal safety as well as their good legal standing to make their art.

In many ways, graffiti writing is a performance of visibility, of ownership, of power—and women graffiti writers are actively reclaiming that power in a male-dominated space. By day, these women are teachers, mothers, citizens; by night, they’re street artists, graffiti grrlz, vandals.

“Everything about Graffiti Grrlz is deviant,” she says. “In terms of gender norms, yes, but also just being citizens in the world. These women embody this double sort of, I don’t give a fuck.”

So women graffiti writers became the natural focus of her graduate thesis. Barring a semester off from school to tackle some family issues, Pabón-Colón immersed herself fully into the world of graffiti culture. At the request of UA’s research ethics board, she had to have her interviewees sign paperwork that promised she wouldn’t exploit them. It was surprisingly uncomplicated given the nature of graffiti: her subjects all signed the slips with their street tags, preserving their anonymity while also keeping Pabón-Colón and UA out of any legal trouble.

Connecting with Women Graffiti Writers

In the beginning, Pabón-Colón primarily used AOL Instant Messaging (AIM) to reach out to women graffiti writers. It was the early 2000s, after all, so AIM and email were still the dominant ways of communicating privately over the Web. (In case you’re curious, her handle was “pfeminist.”)

Social networking was perhaps Pabón-Colón’s greatest research aid. Digital platforms like AIM (and later, Twitter and Facebook) helped her to connect with artists far and wide—and allowed graffiti writers to exercise a customizable degree of anonymity. The Internet was and remains a tool she couldn’t underestimate.

Of course, these interviews were conducted alongside some serious reading: Pabón-Colón hungrily devoured any resources about women graffiti writers—art books, scholarly research, websites—she could find. Too often, women graffiti writers comprised one or two token examples in these texts. Their lack of visibility only fueled her fire.

She flips through pages and pages of AIM transcripts, including an early interview with Miss 17, a New York-based graffiti writer. She’s called the “subcultural king” of the graffiti world, says Pabón-Colón, and for good reason: her commitment to the art form is strong, and her reach is impressive.

“She ended up being the doorway to everybody else,” Pabón-Colón recalls. “Our first bunch of email exchanges were short, cryptic and sporadic, totally unpredictable. But I took a trip to New York to meet up with her in-person. And we clicked.”

Finding sources was a challenge—and getting those sources to open up was often its own battle entirely. Pabón-Colón had to establish herself as a person whose work mattered in this world.

And that’s exactly what she did. With Miss 17 as her point of contact, she forged connections with women graffiti writers on the Web. Soon, women in graffiti culture around the world knew Pabón-Colón and respected her research. In 2004, she was even able to bring four of New York’s most well-known women graffiti writers, including Miss 17, to Tucson to paint a mural.

She connected very organically with these women, but during a heart-to-heart with the group, Pabón-Colón opened up about a realization that rocked her.

I told them I was bummed out and shocked that most graffiti-writing women I’d found didn’t identify as feminists,” she recalls. “And true to form, Claw [one of the writers] spoke up right away. She said, ‘I don’t talk about it; I be about it.’”

Those words were life-changing for Pabón-Colón, who by ‘04 had begun to explore graffiti writing as an act of feminist change, not a product of feminist ideology.

“[I realized] it doesn’t matter to me whether they identify as feminist or not because I know what they’re doing is enacting feminist change within this subculture,” she says. “And that’s what I’m interested in.”

From Graduate Thesis to Book Deal

From 2004 all the way to her final research trip in 2015, the project continued to grow and morph—and Pabón-Colón only grew more and more invested in the topic. She spoke with more than 100 women graffiti writers from all over the world, including on-site interviews with writers in countries like Chile, Brazil, South Africa, France and the Netherlands, to name just a few. Graffiti writers she’d befriended acted as her liaisons, introducing her to other artists as she traveled abroad to expand her research and present her findings at conferences. Again, social media was an invaluable tool: Pabón-Colón would routinely put out calls to friends, fellow scholars and former interviewees for recommendations of local artists to talk to.

In 2012, she gave a talk at a TEDx Women conference, where she spoke about how these women performed feminism—and how their art defied expectations both within and outside of their subcultural bubble.

Her interview process was somewhat streamlined, she told her audience in the TEDx Talk: “The first thing I ask is, ‘What is it like to be a woman in a male-dominated subculture?’ I also ask them, ‘What are the hazards of being a graffiti writer, and why would you take them on in the name of art?’”

At the end of every interview, Pabón-Colón closed with the same question: “What advice would you give to aspiring women graffiti writers?” Responses from her interviewees ran the gamut, but a few key themes emerged: Own your unique style. Find mentors. Don’t quit.

Those interviews eventually became the heart and soul of Pabón-Colón’s doctoral dissertation. In 2013, she graduated with an interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Performance Studies from New York University. By 2016, news of her book contract with NYU Press was public—and Pabón-Colón began to put out calls for cover art from graffiti writers she’d interviewed.

Writing and revising her manuscript was simultaneously a culmination of Pabón-Colón’s work and a reflection on how far the project had come. During the revision process, she was forced to revisit those early documents, the same ones she showed me: the well-loved books, the AIM transcripts, the term paper where it all began.

To this day, she’s grateful for the connections she’s made—and for the social networking sites that allow her to stay in contact with these graffiti grrlz, despite barriers like distance and language.

“They have an investment in my project because it involves their name, but also just women in graffiti,” she says. “It’s been amazing. I also get to do things like use my credentials to help them get things, like grants… Being a doctor has its benefits in terms of cultural capital. And I’m able to watch these women grow as artists.”

How does it feel for Pabón-Colón to witness the culmination of half her lifetime’s worth of work? It’s complicated, she says, but she’s ready to be free to move on to her next project.

“[Publishing this book] is like letting go of my security blanket, my baby,” she says with a laugh. “There will be a moment when there’s a well-known and loved graffiti grrl who I don’t know. And that—that’ll be weird.”

Graffiti Grrlz: Performing Feminism in the Hip Hop Diaspora hit stands on May 1.

Samantha Manzella is a writer, journalist, and editor. A lover of tattoos and iced americanos, she splits her time between Manhattan and upstate New York. Follow her on Twitter (@slmjournalist) and read more of her work at slmjournalist.com.