Historical context surrounding the brutalization of black women’s bodies, and how it continues today.

by Jasmine Rose-Olesco

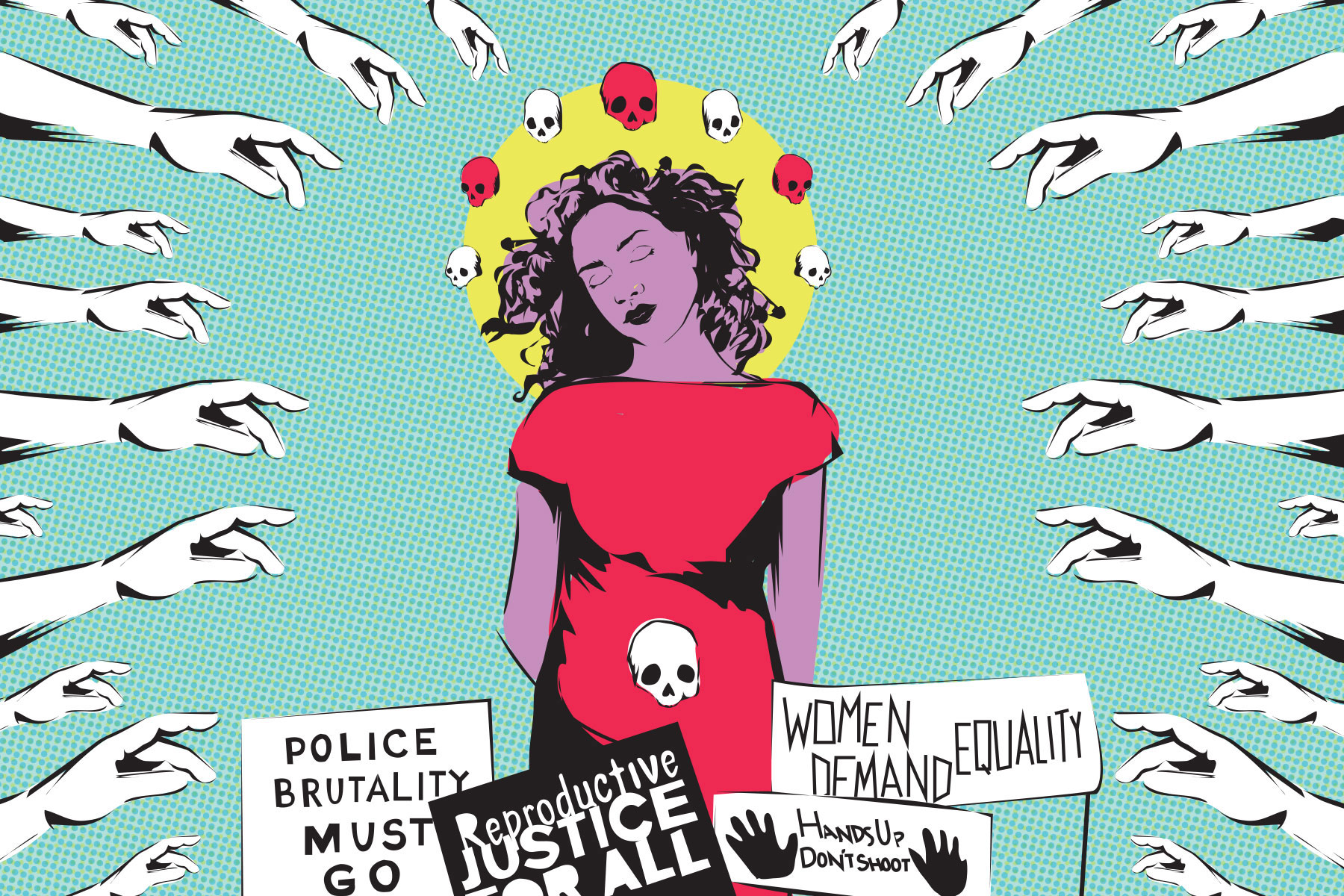

illustration by Grace Molteni

On January 27, 1856, Margaret Garner and her family escaped cruel treatment at the hands of her master, Archibald Gaines. On January 28, when she heard a gun go off in the Cincinnati, Ohio home of her free cousin, Elijah Kite, she immediately slit the throat of her baby, Mary. U.S. Marshals had arrived to pursue her family. An early report of the scene, as the Marshal’s discovered it, was described in the Cincinnati Enquirer on January 29, 1856. The article reads, “a deed of horror had been consummated, for weltering in its blood [was] the throat [of Margaret’s daughter, Mary] being cut from ear to ear and the head almost severed from the body. Upon the floor lay one of the children of the younger couple [Margaret, 22, and her husband, Robert, 25], while in a back room, crouched beneath the bed [were] two more of the children, boys, of two and five years.” Upon this scene of “horror,” Margaret, her family and the other enslaved people traveling with them were apprehended and jailed in the U. S. Marshal’s office as an enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Confirming the source of Mary’s near-decapitation, a report on January 30, 1856 in the Cincinnati Gazette reads: “the mother of the dead child acknowledges she killed it, and that her determination was to have killed all of the children and then destroy herself, rather than return to slavery.”

Lucy Stone, a prominent abolitionist and women’s rights suffragette of the time, held Margaret in high-esteem, as she stated during the heated two week trial of Margaret and her family, “The faded faces of the Negro children tell too plainly to what degradation the female slaves submit. Rather than give her daughter to that life, she killed it. If in her deep, maternal love she felt the impulse to send her child back to God, to save it from coming woe, who shall say she had no right not to do so?” Such words, alluding to the alleged rape of Margaret by her white slave owner, as evidenced by the “faded faces” of her children, were steeped in language that lends itself to the pro-choice and reproductive justice movement of today. Margaret’s final act of autonomy in the role of mother, rather than slave, in the life of her child Mary was a point of contention in a trial that presented itself as a heated legal debate. Questions arose about the definition of murder, the immorality of slavery, and state versus federal jurisdiction — Ohio was classified as a free state while the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was federal law. Ultimately, the judge presiding over the case determined that Margaret and the other captured slaves were liable under the Fugitive Slave Act, effectively returning Margaret and her family to slavery. Margaret, enslaved on a plantation in Mississippi, later died of typhoid fever in 1858, but her legacy proved renewed; acclaimed author Toni Morrison published the 1987 Pulitzer Prize winner, Beloved, the premise inspired by the events of Margaret’s January nights of escape and capture.

Margaret’s horrific experience of whippings, rape and sexual assault at the Maplewood plantation in Boone County, Kentucky, detailed extensively in Modern Medea: A Family Story of Slavery and Child Murder from the Old South(1999) by author Steven Weisenburger, was symptomatic of an institution in which African-American women existed in a paradox. They were deemed as less than human, that is to say, they were not viewed as women under the scrutiny of the law; however, their bodies were highly sexualized and coveted, assaulted and commoditized in the patriarchal way that women’s bodies often are. During this time period, there existed several stereotypes about black womanhood, including that of the “Jezebel.” According to the understanding of black womanhood as delegated by white men of this era, black women were innately sexual creatures, craving sex with their wanton ways. Writing in: Mammy, Jezebel, Sapphire, and Their Homegirls: Developing an Oppositional Gaze Toward the Images of Black Women (2008), Dr. Carolyn West states, “The Jezebel stereotype, which branded black women as sexually promiscuous, was used to justify…sexual atrocities. This image gave the impression that black women could not be rape victims because they always desired sex.” In truth, enslaved black women could not give consent to sexual acts; their bodies were not theirs to speak of, as their flesh and bone, melanin and course hair, labor and self were owned by someone else. In Ain’t I A Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (1999), author Deborah Gray explains that female slaves were also inspected for their reproductive ability, as she states that the stomachs of female slaves who were up for auction were “kneaded” in order to figure out how many children a female slave could bare. Additionally, Gray writes that, “when there was doubt about a woman’s reproductive ability, she was taken by [a slave] buyer and a physician to a private room where she was inspected more thoroughly.”

Margaret’s determination to free her children from bondage and experiences like the ones accounted by Weisenburger, West and Gray was threaded in the fabric of black motherhood in both the enforced journey to the Americas as well as enslaved life in the western hemisphere. Captured African people often committed suicide and infanticide, jumping overboard to the shark-infested water of the Atlantic, rather than succumb to an unknown life in America. Additionally, author Sharon M. Harris writes in Executing Race: Early American Women’s Narratives of Race, Society, and the Law (2005) that in the years between 1670 and 1780, black women [in New England] were tried and convicted of having committed infanticide one and-one half times more than white women, “despite the fact that black [people] constituted only 3 to 4 percent of the New England population.” She also highlights that most cases of infanticide committed by black women were committed by black women who were enslaved. It would seem that a double standard of criminalization concerning black women’s right to autonomy and resistance existed, which, among other things, pathologized black motherhood. Another influence of the pathology of black motherhood was the fact that enslaved black mothers’ children, whether biologically fathered by white slaveowners or not, were held to the status of the mother. This legalized inability for enslaved black women to claim their bodies against sexual advances, rape, and breeding for economic gain gave way to what poet and activist Adrienne Rich regards as “motherhood as enforced identity and as political institution,” which, according to Rich, is distinguishable from the “experience of motherhood.”

Arguably, the legacy of black motherhood during Transatlantic slavery persists today for black women, and black mothers, whose rights to reproduction are arguably devalued when the bodies of their children are brutalized, when their own bodies are barraged with assault, police brutality, sterilization, and damaging sexualized and racialized images. Who’s protecting the reproductive rights of pregnant women of color, specifically black pregnant women, who are brutalized by police in various parts of the country? Who protects the reproductive rights of black trans people who seek access to healthy abortions and the rights of trans women of color who are brutalized by police? Activists within the reproductive justice movement tirelessly work against these denials of civil rights and more.

The reproductive justice movement’s origins can be traced to 1994. Loretta Ross, founder of the “Sister Song” organization and one of the women who coined the phrase “reproductive justice” wrote in “A History of Reproductive Justice” about a group of black women, later called the “Women of African Descent for Reproductive Justice” who caucused at the Illinois Pro-Choice Alliance Conference. These women opposed the potential health care reform campaign from the Clinton Administration because its language did not ensure access to abortions. In an effort to use inclusive language, unlike the word “choice,” which doesn’t accurately “represent communities with few real choices,” these women used phrases like “reproductive rights” and coined the phrase “reproductive justice.” Organizations like Sister Song work to secure human rights for women of color, including black women, whose children are disproportionately poured into the school-to-prison pipeline, are perceived as feeling less physical pain than their white counterparts, are at risk of being killed every 28 hours by a vigilante or police officer, whose black or darker-skinned daughters are suspended from school more than their white counterparts for similar, minor behaviors, and whose offspring with advanced degrees earn, on average, the same as their white counterparts with Bachelor’s degrees. When several anti-abortion billboards from the “Life Always” organization were posted in New York City in 2011, these ads were viewed as targeting black women, specifically. One such billboard stated, “The most dangerous place for an African-American is in the womb,” much to the chagrin of “Sistersong and the Trust Black Women partnership.” The partnership declares pro-lifers’ absence from the conversation about policy advocacy for the lives of people of color in regard to police brutality, access to quality health care, and public education as an act that seeks to diminish the agency of African-American women. The partnership cites American black women’s more than 400-year history of battling racism and sexism and taking autonomy of their health and health care by choosing abortion if it is the best decision for themselves and/or their family.

Like Sister Song, black mothers continue to speak out in resistance against brutality and the rights of their children. According to a September 2014 report by Aisha Sultan for St. Louis Today, black mothers gathered at The Missouri History Museum, telling the audience about their fear for their children given recent reports of police brutality against unarmed black people. The mothers on stage spoke of the “the talk” they had with their children, referring to the advice that black mothers dispense to their children for if and/or when they encounter police, especially in heavily-populated white neighborhoods. One mother cited telling her son to introduce himself to the police department upon moving to a new neighborhood, so if he was ever stopped, the police would recognize him. Other advice from the mothers on stage included advising children to never run from police, even if scared, lest they be shot, to not engage in a group of three or more, as they would be considered a mob by the police, and to never reach for anything in their car when stopped by police. Tears abounded at the talk that included expressions of fear for their children’s lives, while Assata Henderson, a black mother of three sons that became college graduates, expressed that she wondered about the conversations white mothers were having with their children who grew up to be privileged, prominent members of society, including, according to the report, judges, CEOS, and police officers. She asked the white mothers in the racially diverse audience, “You’re the mothers. What are the conversations you are having with the police officers who harass our children?”

The mothers on stage during this event were not alone in their convictions. I spoke with Audra Emmanuel, a registered nurse employed by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, who agreed with a “yes, absolutely,” when asked if she believed if there is a component of racial bias in the policing of black and brown people. While on the phone and walking on her way to work where she advocates for her patients and their mental health capacities, Audra tells me that her millennial sons “think they’re white;” living in a predominately white, suburban neighborhood has made it easy for them to forget their ascribed status as black people. Of the looped, moving images of black men, women and children being killed by bullets, beatings or chokeholds that are splayed across television screens and online media outlets, Audra vehemently responds, “it’s another form of terrorization,” and continues telling me her conviction that these images serve as reminders to black people, like her sons, that they are “nothing.” She recalls her advice to her children in her attempt to aide them in surviving the criminalization of black male bodies like theirs, historically based in what was seen by the United States government as theft of property when slaves rebelled and escaped. In her recollection, Audra cites telling her children that “nothing good happens” at late hours of the night, thus warning them from traveling during late hours, and, perhaps unknowingly, invoking the adages of the mothers on stage in Missouri, when she tells me that her advice to her children is to humble themselves if they encounter police officers. Additionally, as a registered nurse for the Department of Mental Health, Audra Emmanuel tells me during our phone call that the state of race relations in the country prove to be a detriment not only to the physical bodies of black mother and black offspring alike, but to their mental health as well.

In this continued fight, mothers and members of “Mothers for Justice United” marched in Washington, D.C. on May 9 of this year, in honor of mothers whose children were killed by police officers and vigilantes. The march called for an end to police brutality and other forms of racial injustice, as the mothers walked from the U.S. Capitol to the U.S. Department of Justice. Through community building and policy legislation, “Mothers for Justice United” seeks to cease racial injustice.

In recent months, criminalization of black people, reports of police brutality and racial bias in policing have been evidenced by investigations such as the Department of Justice’s extensive report regarding the racial bias of the Ferguson, Missouri Police Department. The investigation was opened on September 4, 2014, approximately one month after the killing of unarmed, black teenager, Michael Brown, 18, by then-police officer Darren Wilson.

The way in which black women seek reclamation of their children’s lives and safety proves complex as a result of reproductive injustice. Video of Toya Graham beating and physically removing her son from the scene of a Baltimore uprising in protest against the death of Freddie Gray, 25, a result of injuries he suffered while in the custody of six Baltimore police officers, has been helmed by some as a heroic, praise-worthy act. Others criticize further violence against black children. The six officers have since been indicted in the death of Freddie Gray, as announced by State’s Attorney for Baltimore, Marilyn Mosby. In response to the outpouring of support and media attention that she has received, Toya tells the Baltimore Sun, “I don’t feel that I am a hero mom…To see my son in that predicament, I had to go out there and do something. I see myself as a regular mom who had to get out there to protect my child.”

For black women, the fight for civil and reproductive rights for themselves and for their children continues. Through calls for policy reform, demonstrations and writing, organizations like Sister Song, Mothers Against Police Brutality, the American Civil Liberties Union, Black Girl Dangerous, Hands Up United and Lambda Legal fight against the profiling and police brutality that disproportionately target black trans and cis women and their children, old and young alike.

[hr style=”striped”]

Jasmine Rose-Olesco is a Boston-based freelance writer, speaker, and activist. Her work has appeared on Time.com, xoJane.com, Refinery29.com, Luckmag.com, Femsplain.com, HelloGiggles.com, and is forthcoming from The Billfold. She currently serves as a Featured Contributor for the fem-powered content community Femsplain.com. A native of Boston, Massachusetts, Jasmine is a student at Boston College in Chestnut Hill. Follow her on Twitter or visit her on Tumblr at arosethatgrew.tumblr.com

Grace Molteni is a Midwest born and raised designer, illustrator, and self-proclaimed bibliophile, currently calling Chicago home. For more musings, work, or just to say hey check her out on Instagram or at her personal website.