How our culture’s obsession with protecting women affected our reaction to the recent tragedies in Nigeria and South Korea.

by Emma Winsor Wood

I did not want to write an essay about violence, power and obsession. I wanted to explore whether the word “girl,” which has been used to refer to unmarried women since the mid-15th century and sparked debates since second-wave feminism, has become less dismissive and more descriptive in the era of extended adolescence popularized on HBO’s Girls. But then the world intervened—first in Nigeria, then in South Korea—and I found myself thinking only about the way we, as a nation, react when tragedies happen to girls.

Boko Haram insurgents, members of an Islamist jihadist sect, have been terrorizing communities in Nigeria since 2002. Fifteen days ago, the group kidnapped about 200 16- to 18-year-old girls, whose school had opened for final exams despite threats directed at schools in the area. Although the Nigerian military claims to be intensifying their search, they have thus far failed in locating the girls. Parents, incensed, have had almost no choice but to sit and wait. One mother said, “We are praying and fasting for the safe return of our daughters.”

Thirteen days ago, the South Korean ferry Sewol sank. Nearly two thirds of its 476 passengers remain unaccounted for. Before the weekend, divers searching for survivors in possible air bubbles discovered a single room filled with 49 drowned high school girls in life jackets. The posted and reposted Associated Press article describes a particularly heart-wrenching scene: “’Bring back my daughter!’ the woman cries, calling out her child’s name in agony.” She has just identified her daughter’s body. “A man rushes over, lifts her on his back and carries her away.”

These two events are nothing but senseless tragedies, enacted upon high school-aged children, which happened to coincide in time, producing sets of waiting and grieving parents in two countries. Since the discovery of the 49 bodies on Sewol, the parallel between the two events has strengthened: now, they are both stories about disappeared girls.

“Girls are going to die,” Buffy repeats again and again in the final season of Joss Whedon’s cult show Buffy the Vampire Slayer. It is a point that Whedon needs to nail down for his viewers, because nothing is worse than girls dying. Girls are cultural symbols of purity, innocence and virtue. They are the embodiment of what civilization has been created to protect. The failure to protect them—to save the girls from dying—represents the ultimate failure of society. It represents the dark, anarchic instinct that seethes close under the surface of everyday life, reaffirming what Thomas Hobbes first expressed in the Leviathan: without organized government and a social contract, there would be no books, no internet, no common decency, just a “war of all against all.”

As a culture, we tend to relish the outrage provoked by bad things happening to girls. Long before there was Buffy, there were fairytales: Cinderella, Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood—dark but mostly hopeful tales about lost girls being rescued. And if a girl wasn’t rescued, like Jonbenet Ramsey, her death would become a repository for the public’s formerly undirected moral outrage: Getting away with the murder of a beautiful girl is worse than getting away with murder. When I worked in book publishing, one of my duties involved typing one- to two-sentence synopses for about 50 novels a week. I wrote hundreds of variations on a theme: When teenage girls start mysteriously disappearing, when two girls go missing, after her 16-year-old daughter vanishes, in the wake of her sister’s apparent suicide, his wife’s murder, girlfriend’s drowning, ad infinitum, ad nauseam, ad lacrimam. This is our favorite story because it reduces the world to a black-and-white moral plane: girls are good, and no one should hurt them.

I have watched the tragedies in Nigeria and South Korea unfold—or rather, stand still—over the past two weeks, with our cultural predilection for dark stories about girls in the back of my mind, and wondered: Why isn’t the media doing more with these stories? Or, as Anne Perkins observed in The Guardian, “200 girls are missing in Nigeria—so why doesn’t anybody care?” Aside from the few heart-wrenching quotations I used above, coverage of both cases has been relatively dry, thankfully free of the prurient detail that so often implicates the viewer in the very acts being decried. In both cases, media access to first-person accounts, which might provide such details, is limited. But even if it were not, I do not believe these events would attract a much greater share of media coverage.

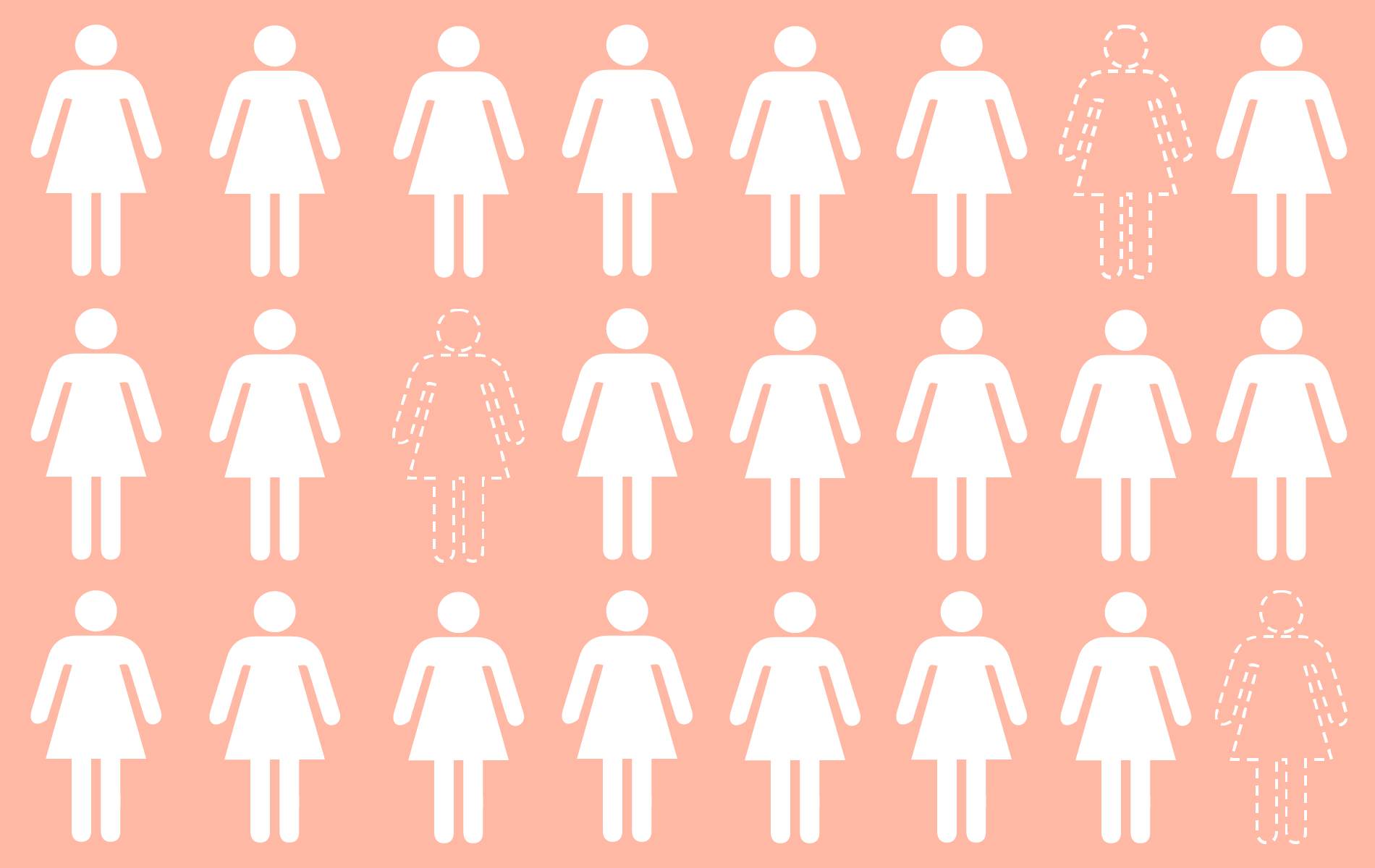

The tragedies in Nigeria and South Korea are not morally ambiguous: we can agree that terrorists, lax boat inspectors, and a seemingly incompetent crew are the respective “bad guys.” And yet, although they fit the criteria, the two stories do not tap into our cultural fetish for the wronged girl. We cannot spin the painful events into romance or suspense. They are global issues that can be harnessed, hopefully, as agents of change. The girls become numbers—200, 49—instead of faces. So we report on them dutifully. I do not want to advocate for sensationalism, but I do wish we could find a productive way to deploy our morbid cultural obsession with the “gone girl”: to raise awareness and money for girls kidnapped in terrorized countries or sold into the sex trade or otherwise wronged in ways that do no make for a good story.

Emma Winsor Wood is a poet and freelance writer. She writes the Women and Words column for TheRiveterMagazine.com. You can find her on Twitter @EmmaWinsorWood.