In a post-feminist world, no one wants to do the wife’s work

by Emma Winsor Wood

No one wants to be a wife anymore. It’s not that no one wants to walk down the aisle in a poofy white dress, change their name, and have 2.5 kids (because they do!), but that no one wants to take on the duties traditionally associated with the title. Being a “wife” means doing all the trivial and sometimes unsavory tasks required to keep a home in working order: the laundry, the party-planning, the dog-walking, the dishes, and the bills. It means subscribing to the notion that domestic activity—even the mindless kind—is eloquent in nature.

It’s boring.

In a recent piece in the Atlantic, Koa Beck asks whether the rarity of selfless, supportive spouses to women presents a potential roadblock to gender parity among writers. While male writers have historically had no trouble finding a “devoted wife” to manage the household (or “a Vera” as Beck refers to them, in reference to Vladimir Nabokov’s famed wife/editor/assistant/cook/secretary/maid), traditional gender roles have made it harder for women writers to find the same. As a result, many successful women writers have hired assistants to complete their to-do list—to be their Vera, their wife—so they can concentrate on their work. If men in the post-feminist age are also having more trouble finding a Vera, the article does not make it known.

And yet I found the piece strangely optimistic—for Beck’s focus on the hired assistant alerted me to the fact that contemporary culture has nearly disassociated the role of the “wife” from gender. “I needed someone to, essentially, be the wife, while I went about the business of being a writer and a mom,” writer Jennifer Weiner is quoted as saying. As long as people have households, the role of the wife is not, and will never be, obsolete; someone needs to perform the tasks traditionally assigned to the position. Today, however, that someone can be the husband, babysitter, personal assistant, Task Rabbit, Roomba—or the wife herself. “Wife” itself, as Weiner’s words indicate, has turned into a title to be earned on the basis of labor division at home.

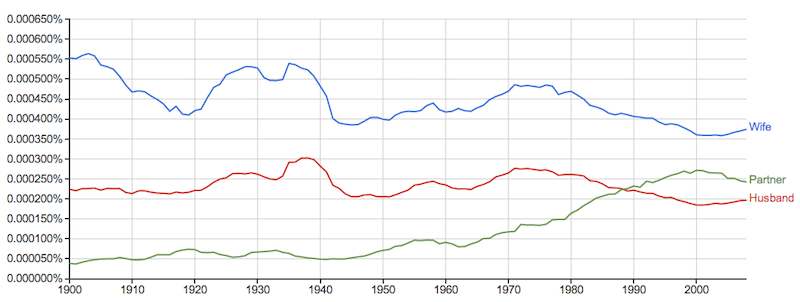

But in a post-feminist world of all-time-low marriage rates, few stay-at-home moms, and the popularization of the word “partner,” an increasing number of homes have no wife at all. The progressive modern couple tends (or tries) to divide housework and parenting more or less equally, and, thanks to the de-stigmatization of divorce, the unhappy wife has the capacity to change her situation without unfair social repercussions. As a result, “wife”—a word associated with a level of female self-sacrifice and dependence that no longer describes the reality of most American households—is becoming an archaic term. A search conducted through the Google Ngram viewer, a tool that graphs word usage over time based on data culled from Google Books, shows that while use of the word “husband” has remained relatively constant over the past century, “wife” hit a century-low in 2000, and “partner” has been on the rise since the 1970s.

- The Google Books Ngram Viewer tracks the usage of certain terms over years of publishing history.

The slight uptick, seen above, in the use of “wife” over the last decade might reflect the recent wave of “wife literature,” i.e. novels like The Paris Wife, American Wife, and The Aviator’s Wife, among many others. These books tap into our common well of nostalgia for a bygone era—an era in which the word “wife” meant something different, something specific. Only that which is fading or gone can be used to evoke nostalgia, which means the wife, like the WASP or the factory worker, belongs to a decaying world. Television shows like Desperate Housewives and Real Housewives series point to the same trend: the housewife has earned our fascination only now that she has become a rarity.

“Wife” has never functioned merely as a descriptive noun: long before Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, the word possessed negative connotations (nagging, jealousy, and greed) it has never been able shake. What’s more, the predominant narrative of the wife in our culture is that of the wronged wife, pitied and scorned in the media after every political scandal, and fully rendered in The Good Wife. In this climate, it’s no wonder that the L.A. clothing brand Dimepiece hit a cultural nerve last year when it released T-shirts emblazoned with the words “Ain’t No Wifey.” It’s not that women don’t want to walk down the aisle in a poofy white dress, change their name, etc.—it’s that most women today don’t want to be somebody’s “wifey.” They want to be women. And in a country where the idea of being Just a Wife is well on its way to becoming a relic of an earlier, primitive time, they can.

Related Content:

Previous volumes of Women & Words:

- Vol. 2, On the Gendered Language of Logic (April 1, 2014)

- Vol. 1, On “Ambitious” Fiction (March 18, 2014)

Emma Winsor Wood is a poet and freelance writer. She writes the Women and Words column for TheRiveterMagazine.com. You can find her on Twitter @EmmaWinsorWood.